| |

The Watch | |

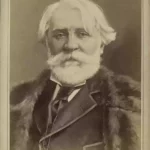

| Author | Ivan S. Turgenev |

|---|---|

| Published |

1846

|

| Language | English |

| Original Language | Russian |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Genre | Realism, Russian Literature |

1846 Short Story

The Watch

The Watch is an English Realism, Russian Literature short story by Russian writer Ivan S. Turgenev. It was first published in 1846. The Watch is Turgenev's timeless story about the fleeting beauty of existence.

The Watch

by Ivan S. Turgenev

AN OLD MAN’S STORY

I

I will tell you my adventures with a watch. It is a curious story.

It happened at the very beginning of this century, in 1801. I had just reached my sixteenth year. I was living at Ryazan in a little wooden house not far from the bank of the river Oka with my father, my aunt and my cousin; my mother I do not remember; she died three years after her marriage; my father had no other children. His name was Porfiry Petrovitch. He was a quiet man, sickly and unattractive in appearance; he was employed in some sort of legal and–other–business. In old days such were called attorneys, sharpers, nettle-seeds; he called himself a lawyer. Our domestic life was presided over by his sister, my aunt, an old maiden lady of fifty; my father, too, had passed his fourth decade. My aunt was very pious, or, to speak bluntly, she was a canting hypocrite and a chattering magpie, who poked her nose into everything; and, indeed, she had not a kind heart like my father. We were not badly off, but had nothing to spare. My father had a brother called Yegor; but he had been sent to Siberia in the year 1797 for some “seditious acts and Jacobin tendencies” (those were the words of the accusation).

Yegor’s son David, my cousin, was left on my father’s hands and lived with us. He was only one year older than I; but I respected him and obeyed him as though he were quite grown up. He was a sensible fellow with character; in appearance, thick-set and broad-shouldered with a square face covered with freckles, with red hair, small grey eyes, thick lips, a short nose, and short fingers–a sturdy lad, in fact–and strong for his age! My aunt could not endure him; my father was positively afraid of him … or perhaps he felt himself to blame towards him. There was a rumour that, if my father had not given his brother away, David’s father would not have been sent to Siberia. We were both at the high school and in the same class and both fairly high up in it; I was, indeed, a little better at my lessons than David. I had a good memory but boys–as we all know!–do not think much of such superiority, and David remained my leader.

II

My name–you know–is Alexey. I was born on the seventh of March and my name-day is the seventeenth. In accordance with the old-fashioned custom, I was given the name of the saint whose festival fell on the tenth day after my birth. My godfather was a certain Anastasy Anastasyevitch Putchkov, or more exactly Nastasey Nastasyeitch, for that was what everyone called him. He was a terribly shifty, pettifogging knave and bribe-taker–a thoroughly bad man; he had been turned out of the provincial treasury and had had to stand his trial on more than one occasion; he was often of use to my father…. They used to “do business” together. In appearance he was a round, podgy figure; and his face was like a fox’s with a nose like an owl’s. His eyes were brown, bright, also like a fox’s, and he was always moving them, those eyes, to right and to left, and he twitched his nose, too, as though he were sniffing the air. He wore shoes without heels, and wore powder every day, which was looked upon as very exceptional in the provinces. He used to declare that he could not go without powder as he had to associate with generals and their ladies. Well, my name-day had come. Nastasey Nastasyeitch came to the house and said:

“I have never made you a present up to now, godson, but to make up for that, look what a fine thing I have brought you to-day.”

And he took out of his pocket a silver watch, a regular turnip, with a rose tree engraved on the face and a brass chain. I was overwhelmed with delight, while my aunt, Pelageya Petrovna, shouted at the top of her voice:

“Kiss his hand, kiss his hand, dirty brat!”

I proceeded to kiss my godfather’s hand, while my aunt went piping on:

“Oh, Nastasey Nastasyeitch! Why do you spoil him like this? How can he take care of a watch? He will be sure to drop it, break it, or spoil it.”

My father walked in, looked at the watch, thanked Nastasey Nastasyeitch–somewhat carelessly, and invited him to his study. And I heard my father say, as though to himself:

“If you think to get off with that, my man….” But I could not stay still. I put on the watch and rushed headlong to show my present to David.

III

David took the watch, opened it and examined it attentively. He had great mechanical ability; he liked having to do with iron, copper, and metals of all sorts; he had provided himself with various instruments, and it was nothing for him to mend or even to make a screw, a key or anything of that kind.

David turned the watch about in his hands and muttering through his teeth (he was not talkative as a rule):

“Oh … poor …” added, “where did you get it?”

I told him that my godfather had given it me.

David turned his little grey eyes upon me:

“Nastasey?”

“Yes, Nastasey Nastasyeitch.”

David laid the watch on the table and walked away without a word.

“Do you like it?” I asked.

“Well, it isn’t that…. But if I were you, I would not take any sort of present from Nastasey.”

“Why?”

“Because he is a contemptible person; and you ought not to be under an obligation to a contemptible person. And to say thank you to him, too. I suppose you kissed his hand?”

“Yes, Aunt made me.”

David grinned–a peculiar grin–to himself. That was his way. He never laughed aloud; he considered laughter a sign of feebleness.

David’s words, his silent grin, wounded me deeply. “So he inwardly despises me,” I thought. “So I, too, am contemptible in his eyes. He would never have stooped to this himself! He would not have accepted presents from Nastasey. But what am I to do now?”

Give back the watch? Impossible!

I did try to talk to David, to ask his advice. He told me that he never gave advice to anyone and that I had better do as I thought best. As I thought best!! I remember I did not sleep all night afterwards: I was in agonies of indecision. I was sorry to lose the watch–I had laid it on the little table beside my bed; its ticking was so pleasant and amusing … but to feel that David despised me (yes, it was useless to deceive myself, he did despise me) … that seemed to me unbearable. Towards morning a determination had taken shape in me … I wept, it is true–but I fell asleep upon it, and as soon as I woke up, I dressed in haste and ran out into the street. I had made up my mind to give my watch to the first poor person I met.

IV

I had not run far from home when I hit upon what I was looking for. I came across a barelegged boy of ten, a ragged urchin, who was often hanging about near our house. I dashed up to him at once and, without giving him or myself time to recover, offered him my watch.

The boy stared at me round-eyed, put one hand before his mouth, as though he were afraid of being scalded–and held out the other.

“Take it, take it,” I muttered, “it’s mine, I give it you, you can sell it, and buy yourself … something you want…. Good-bye.”

I thrust the watch into his hand–and went home at a gallop. Stopping for a moment at the door of our common bedroom to recover my breath, I went up to David who had just finished dressing and was combing his hair.

“Do you know what, David?” I said in as unconcerned a tone as I could, “I have given away Nastasey’s watch.”

David looked at me and passed the brush over his temples.

“Yes,” I added in the same businesslike voice, “I have given it away. There is a very poor boy, a beggar, you know, so I have given it to him.”

David put down the brush on the washing-stand.

“He can buy something useful,” I went on, “with the money he can get for it. Anyway, he will get something for it.”

I paused.

“Well,” David said at last, “that’s a good thing,” and he went off to the schoolroom. I followed him.

“And if they ask you what you have done with it?” he said, turning to me.

“I shall tell them I’ve lost it,” I answered carelessly.

No more was said about the watch between us that day; but I had the feeling that David not only approved of what I had done but … was to some extent surprised by it. He really was!

V

Two days more passed. It happened that no one in the house thought of the watch. My father was taken up with a very serious unpleasantness with one of his clients; he had no attention to spare for me or my watch. I, on the other hand, thought of it without ceasing! Even the approval … the presumed approval of David did not quite comfort me. He did not show it in any special way: the only thing he said, and that casually, was that he hadn’t expected such recklessness of me. Certainly I was a loser by my sacrifice: it was not counter-balanced by the gratification afforded me by my vanity.

And what is more, as ill-luck would have it, another schoolfellow of ours, the son of the town doctor, must needs turn up and begin boasting of a new watch, a present from his grandmother, and not even a silver, but a pinch-back one….

I could not bear it, at last, and, without a word to anyone, slipped out of the house and proceeded to hunt for the beggar boy to whom I had given my watch.

I soon found him; he was playing knucklebones in the churchyard with some other boys.

I called him aside–and, breathless and stammering, told him that my family were angry with me for having given away the watch–and that if he would consent to give it back to me I would gladly pay him for it…. To be ready for any emergency, I had brought with me an old-fashioned rouble of the reign of Elizabeth, which represented the whole of my fortune.

“But I haven’t got it, your watch,” answered the boy in an angry and tearful voice; “my father saw it and took it away from me; and he was for thrashing me, too. ‘You must have stolen it from somewhere,’ he said. ‘What fool is going to make you a present of a watch?'”

“And who is your father?”

“My father? Trofimitch.”

“But what is he? What’s his trade?”

“He is an old soldier, a sergeant. And he has no trade at all. He mends old shoes, he re-soles them. That’s all his trade. That’s what he lives by.”

“Where do you live? Take me to him.”

“To be sure I will. You tell my father that you gave me the watch. For he keeps pitching into me, and calling me a thief! And my mother, too. ‘Who is it you are taking after,’ she says, ‘to be a thief?'”

I set off with the boy to his home. They lived in a smoky hut in the back-yard of a factory, which had long ago been burnt down and not rebuilt. We found both Trofimitch and his wife at home. The discharged sergeant was a tall old man, erect and sinewy, with yellowish grey whiskers, an unshaven chin and a perfect network of wrinkles on his cheeks and forehead. His wife looked older than he. Her red eyes, which looked buried in her unhealthily puffy face, kept blinking dejectedly. Some sort of dark rags hung about them by way of clothes.

I explained to Trofimitch what I wanted and why I had come. He listened to me in silence without once winking or moving from me his stupid and strained–typically soldierly–eyes.

“Whims and fancies!” he brought out at last in a husky, toothless bass. “Is that the way gentlemen behave? And if Petka really did not steal the watch–then I’ll give him one for that! To teach him not to play the fool with little gentlemen! And if he did steal it, then I would give it to him in a very different style, whack, whack, whack! With the flat of a sword; in horseguard’s fashion! No need to think twice about it! What’s the meaning of it? Eh? Go for them with sabres! Here’s a nice business! Tfoo!”

This last interjection Trofimitch pronounced in a falsetto. He was obviously perplexed.

“If you are willing to restore the watch to me,” I explained to him–I did not dare to address him familiarly in spite of his being a soldier–“I will with pleasure pay you this rouble here. The watch is not worth more, I imagine.”

“Well!” growled Trofimitch, still amazed and, from old habit, devouring me with his eyes as though I were his superior officer. “It’s a queer business, eh? Well, there it is, no understanding it. Ulyana, hold your tongue!” he snapped out at his wife who was opening her mouth. “Here’s the watch,” he added, opening the table drawer; “if it really is yours, take it by all means; but what’s the rouble for? Eh?”

“Take the rouble, Trofimitch, you senseless man,” wailed his wife. “You have gone crazy in your old age! We have not a half-rouble between us, and then you stand on your dignity! It was no good their cutting off your pigtail, you are a regular old woman just the same! How can you go on like that–when you know nothing about it? … Take the money, if you have a fancy to give back the watch!”

“Ulyana, hold your tongue, you dirty slut!” Trofimitch repeated. “Whoever heard of such a thing, talking away? Eh? The husband is the head; and yet she talks! Petka, don’t budge, I’ll kill you…. Here’s the watch!”

Trofimitch held out the watch to me, but did not let go of it.

He pondered, looked down, then fixed the same intent, stupid stare upon me. Then all at once bawled at the top of his voice:

“Where is it? Where’s your rouble?”

“Here it is, here it is,” I responded hurriedly and I snatched the coin out of my pocket.

But he did not take it, he still stared at me. I laid the rouble on the table. He suddenly brushed it into the drawer, thrust the watch into my hand and wheeling to the left with a loud stamp, he hissed at his wife and his son:

“Get along, you low wretches!”

Ulyana muttered something, but I had already dashed out into the yard and into the street. Thrusting the watch to the very bottom of my pocket and clutching it tightly in my hand, I hurried home.

VI

I had regained the possession of my watch but it afforded me no satisfaction whatever. I did not venture to wear it, it was above all necessary to conceal from David what I had done. What would he think of me, of my lack of will? I could not even lock up the luckless watch in a drawer: we had all our drawers in common. I had to hide it, sometimes on the top of the cupboard, sometimes under my mattress, sometimes behind the stove…. And yet I did not succeed in hoodwinking David.

One day I took the watch from under a plank in the floor of our room and proceeded to rub the silver case with an old chamois leather glove. David had gone off somewhere in the town; I did not at all expect him to be back quickly…. Suddenly he was in the doorway.

I was so overcome that I almost dropped the watch, and, utterly disconcerted, my face painfully flushing crimson, I fell to fumbling about my waistcoat with it, unable to find my pocket.

David looked at me and, as usual, smiled without speaking.

“What’s the matter?” he brought out at last. “You imagined I didn’t know you had your watch again? I saw it the very day you brought it back.”

“I assure you,” I began, almost on the point of tears….

David shrugged his shoulders.

“The watch is yours, you are free to do what you like with it.”

Saying these cruel words, he went out.

I was overwhelmed with despair. This time there could be no doubt! David certainly despised me.

I could not leave it so.

“I will show him,” I thought, clenching my teeth, and at once with a firm step I went into the passage, found our page-boy, Yushka, and presented him with the watch!

Yushka would have refused it, but I declared that if he did not take the watch from me I would smash it that very minute, trample it under foot, break it to bits and throw it in the cesspool! He thought a moment, giggled, and took the watch. I went back to our room and seeing David reading there, I told him what I had done.

David did not take his eyes off the page and, again shrugging his shoulder and smiling to himself, repeated that the watch was mine and that I was free to do what I liked with it.

But it seemed to me that he already despised me a little less.

I was fully persuaded that I should never again expose myself to the reproach of weakness of character, for the watch, the disgusting present from my disgusting godfather, had suddenly grown so distasteful to me that I was quite incapable of understanding how I could have regretted it, how I could have begged for it back from the wretched Trofimitch, who had, moreover, the right to think that he had treated me with generosity.

Several days passed…. I remember that on one of them the great news reached our town that the Emperor Paul was dead and his son Alexandr, of whose graciousness and humanity there were such favourable rumours, had ascended the throne. This news excited David intensely: the possibility of seeing–of shortly seeing–his father occurred to him at once. My father was delighted, too.

“They will bring back all the exiles from Siberia now and I expect brother Yegor will not be forgotten,” he kept repeating, rubbing his hands, coughing and, at the same time, seeming rather nervous.

David and I at once gave up working and going to the high school; we did not even go for walks but sat in a corner counting and reckoning in how many months, in how many weeks, in how many days “brother Yegor” ought to come back and where to write to him and how to go to meet him and in what way we should begin to live afterwards. “Brother Yegor” was an architect: David and I decided that he ought to settle in Moscow and there build big schools for poor people and we would go to be his assistants. The watch, of course, we had completely forgotten; besides, David had new cares…. Of them I will speak later, but the watch was destined to remind us of its existence again.

VII

One morning we had only just finished lunch–I was sitting alone by the window thinking of my uncle’s release–outside there was the steam and glitter of an April thaw–when all at once my aunt, Pelageya Petrovna, walked into the room. She was at all times restless and fidgetty, she spoke in a shrill voice and was always waving her arms about; on this occasion she simply pounced on me.

“Go along, go to your father at once, sir!” she snapped out. “What pranks have you been up to, you shameless boy! You will catch it, both of you. Nastasey Nastasyeitch has shown up all your tricks! Go along, your father wants you…. Go along this very minute.”

Understanding nothing, I followed my aunt, and, as I crossed the threshold of the drawing-room, I saw my father, striding up and down and ruffling up his hair, Yushka in tears by the door and, sitting on a chair in the corner, my godfather, Nastasey Nastasyeitch, with an expression of peculiar malignancy in his distended nostrils and in his fiery, slanting eyes.

My father swooped down upon me as soon as I walked in.

“Did you give your watch to Yushka? Tell me!”

I glanced at Yushka.

“Tell me,” repeated my father, stamping.

“Yes,” I answered, and immediately received a stinging slap in the face, which afforded my aunt great satisfaction. I heard her gulp, as though she had swallowed some hot tea. From me my father ran to Yushka.

“And you, you rascal, ought not to have dared to accept such a present,” he said, pulling him by the hair: “and you sold it, too, you good-for-nothing boy!”

Yushka, as I learned later had, in the simplicity of his heart, taken my watch to a neighbouring watchmaker’s. The watchmaker had displayed it in his shop-window; Nastasey Nastasyeitch had seen it, as he passed by, bought it and brought it along with him.

However, my ordeal and Yushka’s did not last long: my father gasped for breath, and coughed till he choked; indeed, it was not in his character to be angry long.

“Brother, Porfiry Petrovitch,” observed my aunt, as soon as she noticed not without regret that my father’s anger had, so to speak, flickered out, “don’t you worry yourself further: it’s not worth dirtying your hands over. I tell you what I suggest: with the consent of our honoured friend, Nastasey Nastasyeitch, in consideration of the base ingratitude of your son–I will take charge of the watch; and since he has shown by his conduct that he is not worthy to wear it and does not even understand its value, I will present it in your name to a person who will be very sensible of your kindness.”

“Whom do you mean?” asked my father.

“To Hrisanf Lukitch,” my aunt articulated, with slight hesitation.

“To Hrisashka?” asked my father, and with a wave of his hand, he added: “It’s all one to me. You can throw it in the stove, if you like.”

He buttoned up his open vest and went out, writhing from his coughing.

“And you, my good friend, do you agree?” said my aunt, addressing Nastasey Nastasyeitch.

“I am quite agreeable,” responded the latter. During the whole proceedings he had not stirred and only snorting stealthily and stealthily rubbing the ends of his fingers, had fixed his foxy eyes by turns on me, on my father, and on Yushka. We afforded him real gratification!

My aunt’s suggestion revolted me to the depths of my soul. It was not that I regretted the watch; but the person to whom she proposed to present it was absolutely hateful to me. This Hrisanf Lukitch (his surname was Trankvillitatin), a stalwart, robust, lanky divinity student, was in the habit of coming to our house–goodness knows what for!–to help the children with their lessons, my aunt asserted; but he could not help us with our lessons because he had never learnt anything himself and was as stupid as a horse. He was rather like a horse altogether: he thudded with his feet as though they had been hoofs, did not laugh but neighed, opening his jaws till you could see right down his throat–and he had a long face, a hooked nose and big, flat jaw-bones; he wore a shaggy frieze, full-skirted coat, and smelt of raw meat. My aunt idolised him and called him a good-looking man, a cavalier and even a grenadier. He had a habit of tapping children on the forehead with the nails of his long fingers, hard as stones (he used to do it to me when I was younger), and as he tapped he would chuckle and say with surprise: “How your head resounds, it must be empty.” And this lout was to possess my watch!–No, indeed, I determined in my own mind as I ran out of the drawing-room and flung myself on my bed, while my cheek glowed crimson from the slap I had received and my heart, too, was aglow with the bitterness of the insult and the thirst for revenge–no, indeed! I would not allow that cursed Hrisashka to jeer at me…. He would put on the watch, let the chain hang over his stomach, would neigh with delight; no, indeed!

“Quite so, but how was it to be done, how to prevent it?”

I determined to steal the watch from my aunt.

VIII

Luckily Trankvillitatin was away from the town at the time: he could not come to us before the next day; I must take advantage of the night! My aunt did not lock her bedroom door and, indeed, none of the keys in the house would turn in the locks; but where would she put the watch, where would she hide it? She kept it in her pocket till the evening and even took it out and looked at it more than once; but at night–where would it be at night?–Well, that was just my work to find out, I thought, shaking my fists.

I was burning with boldness and terror and joy at the thought of the approaching crime. I was continually nodding to myself; I knitted my brows. I whispered: “Wait a bit!” I threatened someone, I was wicked, I was dangerous … and I avoided David!–no one, not even he, must have the slightest suspicion of what I meant to do….

I would act alone and alone I would answer for it!

Slowly the day lagged by, then the evening, at last the night came. I did nothing; I even tried not to move: one thought was stuck in my head like a nail. At dinner my father, who was, as I have said, naturally gentle, and who was a little ashamed of his harshness–boys of sixteen are not slapped in the face–tried to be affectionate to me; but I rejected his overtures, not from slowness to forgive, as he imagined at the time, but simply that I was afraid of my feelings getting the better of me; I wanted to preserve untouched all the heat of my vengeance, all the hardness of unalterable determination. I went to bed very early; but of course I did not sleep and did not even shut my eyes, but on the contrary opened them wide, though I did pull the quilt over my head. I did not consider beforehand how to act. I had no plan of any kind; I only waited till everything should be quiet in the house. I only took one step: I did not remove my stockings. My aunt’s room was on the second floor. One had to pass through the dining-room and the hall, go up the stairs, pass along a little passage and there … on the right was the door! I must not on any account take with me a candle or a lantern; in the corner of my aunt’s room a little lamp was always burning before the ikon shrine; I knew that. So I should be able to see. I still lay with staring eyes and my mouth open and parched; the blood was throbbing in my temples, in my ears, in my throat, in my back, all over me! I waited … but it seemed as though some demon were mocking me; time passed and passed but still silence did not reign.

IX

Never, I thought, had David been so late getting to sleep…. David, the silent David, even began talking to me! Never had they gone on so long banging, talking, walking about the house! And what could they be talking about? I wondered; as though they had not had the whole day to talk in! Sounds outside persisted, too; first a dog barked on a shrill, obstinate note; then a drunken peasant was making an uproar somewhere and would not be pacified; then gates kept creaking; then a wretched cart on racketty wheels kept passing and passing and seeming as though it would never pass! However, these sounds did not worry me: on the contrary, I was glad of them; they seemed to distract my attention. But now at last it seemed as though all were tranquil. Only the pendulum of our old clock ticked gravely and drowsily in the dining-room and there was an even drawn-out sound like the hard breathing of people asleep. I was on the point of getting up, then again something rustled … then suddenly sighed, something soft fell down … and a whisper glided along the walls.

Or was there nothing of the sort–and was it only imagination mocking me?

At last all was still. It was the very heart, the very dead of night. The time had come! Chill with anticipation, I threw off the bedclothes, let my feet down to the floor, stood up … one step; a second…. I stole along, my feet, heavy as though they did not belong to me, trod feebly and uncertainly. Stay! what was that sound? Someone sawing, somewhere, or scraping … or sighing? I listened … I felt my cheeks twitching and cold watery tears came into my eyes. Nothing! … I stole on again. It was dark but I knew the way. All at once I stumbled against a chair…. What a bang and how it hurt! It hit me just on my leg…. I stood stock still. Well, did that wake them? Ah! here goes! Suddenly I felt bold and even spiteful. On! On! Now the dining-room was crossed, then the door was groped for and opened at one swing. The cursed hinge squeaked, bother it! Then I went up the stairs, one! two! one! two! A step creaked under my foot; I looked at it spitefully, just as though I could see it. Then I stretched for the handle of another door. This one made not the slightest sound! It flew open so easily, as though to say, “Pray walk in.” … And now I was in the corridor!

In the corridor there was a little window high up under the ceiling, a faint light filtered in through the dark panes. And in that glimmer of light I could see our little errand girl lying on the floor on a mat, both arms behind her tousled head; she was sound asleep, breathing rapidly and the fatal door was just behind her head. I stepped across the mat, across the girl … who opened that door? … I don’t know, but there I was in my aunt’s room. There was the little lamp in one corner and the bed in the other and my aunt in her cap and night jacket on the bed with her face towards me. She was asleep, she did not stir, I could not even hear her breathing. The flame of the little lamp softly flickered, stirred by the draught of fresh air, and shadows stirred all over the room, even over the motionless wax-like yellow face of my aunt….

And there was the watch! It was hanging on a little embroidered cushion on the wall behind the bed. What luck, only think of it! Nothing to delay me! But whose steps were those, soft and rapid behind my back? Oh! no! it was my heart beating! … I moved my legs forward…. Good God! something round and rather large pushed against me below my knee, once and again! I was ready to scream, I was ready to drop with horror…. A striped cat, our own cat, was standing before me arching his back and wagging his tail. Then he leapt on the bed–softly and heavily–turned round and sat without purring, exactly like a judge; he sat and looked at me with his golden pupils. “Puss, puss,” I whispered, hardly audibly. I bent across my aunt, I had already snatched the watch. She suddenly sat up and opened her eyelids wide…. Heavenly Father, what next? … but her eyelids quivered and closed and with a faint murmur her head sank on the pillow.

A minute later I was back again in my own room, in my own bed and the watch was in my hands….

More lightly than a feather I flew back! I was a fine fellow, I was a thief, I was a hero, I was gasping with delight, I was hot, I was gleeful–I wanted to wake David at once to tell him all about it–and, incredible as it sounds, I fell asleep and slept like the dead! At last I opened my eyes…. It was light in the room, the sun had risen. Luckily no one was awake yet. I jumped up as though I had been scalded, woke David and told him all about it. He listened, smiled. “Do you know what?” he said to me at last, “let’s bury the silly watch in the earth, so that it may never be seen again.” I thought his idea best of all. In a few minutes we were both dressed; we ran out into the orchard behind our house and under an old apple tree in a deep hole, hurriedly scooped out in the soft, springy earth with David’s big knife, my godfather’s hated present was hidden forever, so that it never got into the hands of the disgusting Trankvillitatin after all! We stamped down the hole, strewed rubbish over it and, proud and happy, unnoticed by anyone, went home again, got into our beds and slept another hour or two–and such a light and blissful sleep!

X

You can imagine the uproar there was that morning, as soon as my aunt woke up and missed the watch! Her piercing shriek is ringing in my ears to this day. “Help! Robbed! Robbed!” she squealed, and alarmed the whole household. She was furious, while David and I only smiled to ourselves and sweet was our smile to us. “Everyone, everyone must be well thrashed!” bawled my aunt. “The watch has been stolen from under my head, from under my pillow!” We were prepared for anything, we expected trouble…. But contrary to our expectations we did not get into trouble at all. My father certainly did fume dreadfully at first, he even talked of the police; but I suppose he was bored with the enquiry of the day before and suddenly, to my aunt’s indescribable amazement, he flew out not against us but against her.

“You sicken me worse than a bitter radish, Pelageya Petrovna,” he shouted, “with your watch. I don’t want to hear any more about it! It can’t be lost by magic, you say, but what’s it to do with me? It may be magic for all I care! Stolen from you? Well, good luck to it then! What will Nastasey Nastasyeitch say? Damnation take him, your Nastasyeitch! I get nothing but annoyances and unpleasantness from him! Don’t dare to worry me again! Do you hear?”

My father slammed the door and went off to his own room. David and I did not at first understand the allusion in his last words; but afterwards we found out that my father was just then viol