| |

The Courtship of Susan Bell | |

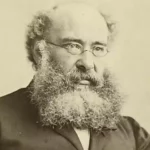

| Author | Anthony Trollope |

|---|---|

| Published |

1844

|

| Language | English |

| Nationality | British |

| Genre | Social Commentary, Victorian Literature |

1844 Short Story

The Courtship of Susan Bell

The Courtship of Susan Bell is an English Social Commentary, Victorian Literature short story by British writer Anthony Trollope. It was first published in 1844.

The Courtship of Susan Bell

by Anthony Trollope

John Munroe Bell had been a lawyer in Albany, State of New York, and as such had thriven well. He had thriven well as long as thrift and thriving on this earth had been allowed to him. But the Almighty had seen fit to shorten his span.

Early in life he had married a timid, anxious, pretty, good little wife, whose whole heart and mind had been given up to do his bidding and deserve his love. She had not only deserved it but had possessed it, and as long as John Munroe Bell had lived, Henrietta Bell–Hetta as he called her–had been a woman rich in blessings. After twelve years of such blessings he had left her, and had left with her two daughters, a second Hetta, and the heroine of our little story, Susan Bell.

A lawyer in Albany may thrive passing well for eight or ten years, and yet not leave behind him any very large sum of money if he dies at the end of that time. Some small modicum, some few thousand dollars, John Bell had amassed, so that his widow and daughters were not absolutely driven to look for work or bread.

In those happy days when cash had begun to flow in plenteously to the young father of the family, he had taken it into his head to build for himself, or rather for his young female brood, a small neat house in the outskirts of Saratoga Springs. In doing so he was instigated as much by the excellence of the investment for his pocket as by the salubrity of the place for his girls. He furnished the house well, and then during some summer weeks his wife lived there, and sometimes he let it.

How the widow grieved when the lord of her heart and master of her mind was laid in the grave, I need not tell. She had already counted ten years of widowhood, and her children had grown to be young women beside her at the time of which I am now about to speak. Since that sad day on which they had left Albany they had lived together at the cottage at the Springs. In winter their life had been lonely enough; but as soon as the hot weather began to drive the fainting citizens out from New York, they had always received two or three boarders–old ladies generally, and occasionally an old gentleman–persons of very steady habits, with whose pockets the widow’s moderate demands agreed better than the hotel charges. And so the Bells lived for ten years.

That Saratoga is a gay place in July, August, and September, the world knows well enough. To girls who go there with trunks full of muslin and crinoline, for whom a carriage and pair of horses is always waiting immediately after dinner, whose fathers’ pockets are bursting with dollars, it is a very gay place. Dancing and flirtations come as a matter of course, and matrimony follows after with only too great rapidity. But the place was not very gay for Hetta or Susan Bell.

In the first place the widow was a timid woman, and among other fears feared greatly that she should be thought guilty of setting traps for husbands. Poor mothers! how often are they charged with this sin when their honest desires go no further than that their bairns may be “respectit like the lave.” And then she feared flirtations; flirtations that should be that and nothing more, flirtations that are so destructive of the heart’s sweetest essence. She feared love also, though she longed for that as well as feared it;–for her girls, I mean; all such feelings for herself were long laid under ground;–and then, like a timid creature as she was, she had other indefinite fears, and among them a great fear that those girls of hers would be left husbandless,–a phase of life which after her twelve years of bliss she regarded as anything but desirable. But the upshot was,–the upshot of so many fears and such small means,–that Hetta and Susan Bell had but a dull life of it.

Were it not that I am somewhat closely restricted in the number of my pages, I would describe at full the merits and beauties of Hetta and Susan Bell. As it is I can but say a few words. At our period of their lives Hetta was nearly one-and-twenty, and Susan was just nineteen. Hetta was a short, plump, demure young woman, with the softest smoothed hair, and the brownest brightest eyes. She was very useful in the house, good at corn cakes, and thought much, particularly in these latter months, of her religious duties. Her sister in the privacy of their own little room would sometimes twit her with the admiring patience with which she would listen to the lengthened eloquence of Mr. Phineas Beckard, the Baptist minister. Now Mr. Phineas Beckard was a bachelor.

Susan was not so good a girl in the kitchen or about the house as was her sister; but she was bright in the parlour, and if that motherly heart could have been made to give out its inmost secret– which however, it could not have been made to give out in any way painful to dear Hetta–perhaps it might have been found that Susan was loved with the closest love. She was taller than her sister, and lighter; her eyes were blue as were her mother’s; her hair was brighter than Hetta’s, but not always so singularly neat. She had a dimple on her chin, whereas Hetta had none; dimples on her cheeks too, when she smiled; and, oh, such a mouth! There; my allowance of pages permits no more.

One piercing cold winter’s day there came knocking at the widow’s door–a young man. Winter days, when the ice of January is refrozen by the wind of February, are very cold at Saratoga Springs. In these days there was not often much to disturb the serenity of Mrs. Bell’s house; but on the day in question there came knocking at the door–a young man.

Mrs. Bell kept an old domestic, who had lived with them in those happy Albany days. Her name was Kate O’Brien, but though picturesque in name she was hardly so in person. She was a thick- set, noisy, good-natured old Irishwoman, who had joined her lot to that of Mrs. Bell when the latter first began housekeeping, and knowing when she was well off; had remained in the same place from that day forth. She had known Hetta as a baby, and, so to say, had seen Susan’s birth.

“And what might you be wanting, sir?” said Kate O’Brien, apparently not quite pleased as she opened the door and let in all the cold air.

“I wish to see Mrs. Bell. Is not this Mrs. Bell’s house?” said the young man, shaking the snow from out of the breast of his coat.

He did see Mrs. Bell, and we will now tell who he was, and why he had come, and how it came to pass that his carpet-bag was brought down to the widow’s house and one of the front bedrooms was prepared for him, and that he drank tea that night in the widow’s parlour.

His name was Aaron Dunn, and by profession he was an engineer. What peculiar misfortune in those days of frost and snow had befallen the line of rails which runs from Schenectady to Lake Champlain, I never quite understood. Banks and bridges had in some way come to grief, and on Aaron Dunn’s shoulders was thrown the burden of seeing that they were duly repaired. Saratoga Springs was the centre of these mishaps, and therefore at Saratoga Springs it was necessary that he should take up his temporary abode.

Now there was at that time in New York city a Mr. Bell, great in railway matters–an uncle of the once thriving but now departed Albany lawyer. He was a rich man, but he liked his riches himself; or at any rate had not found himself called upon to share them with the widow and daughters of his nephew. But when it chanced to come to pass that he had a hand in despatching Aaron Dunn to Saratoga, he took the young man aside and recommended him to lodge with the widow. “There,” said he, “show her my card.” So much the rich uncle thought he might vouchsafe to do for the nephew’s widow.

Mrs. Bell and both her daughters were in the parlour when Aaron Dunn was shown in, snow and all. He told his story in a rough, shaky voice, for his teeth chattered; and he gave the card, almost wishing that he had gone to the empty big hotel, for the widow’s welcome was not at first quite warm.

The widow listened to him as he gave his message, and then she took the card and looked at it. Hetta, who was sitting on the side of the fireplace facing the door, went on demurely with her work. Susan gave one glance round–her back was to the stranger–and then another; and then she moved her chair a little nearer to the wall, so as to give the young man room to come to the fire, if he would. He did not come, but his eyes glanced upon Susan Bell; and he thought that the old man in New York was right, and that the big hotel would be cold and dull. It was a pretty face to look on that cold evening as she turned it up from the stocking she was mending.

“Perhaps you don’t wish to take winter boarders, ma’am?” said Aaron Dunn.

“We never have done so yet, sir,” said Mrs. Bell timidly. Could she let this young wolf in among her lamb-fold? He might be a wolf;– who could tell?

“Mr. Bell seemed to think it would suit,” said Aaron.

Had he acquiesced in her timidity and not pressed the point, it would have been all up with him. But the widow did not like to go against the big uncle; and so she said, “Perhaps it may, sir.”

“I guess it will, finely,” said Aaron. And then the widow seeing that the matter was so far settled, put down her work and came round into the passage. Hetta followed her, for there would be housework to do. Aaron gave himself another shake, settled the weekly number of dollars–with very little difficulty on his part, for he had caught another glance at Susan’s face; and then went after his bag. ‘Twas thus that Aaron Dunn obtained an entrance into Mrs. Bell’s house. “But what if he be a wolf?” she said to herself over and over again that night, though not exactly in those words. Ay, but there is another side to that question. What if he be a stalwart man, honest-minded, with clever eye, cunning hand, ready brain, broad back, and warm heart; in want of a wife mayhap; a man that can earn his own bread and another’s;–half a dozen others’ when the half dozen come? Would not that be a good sort of lodger? Such a question as that too did flit, just flit, across the widow’s sleepless mind. But then she thought so much more of the wolf! Wolves, she had taught herself to think, were more common than stalwart, honest-minded, wife-desirous men.

“I wonder mother consented to take him,” said Hetta, when they were in the little room together.

“And why shouldn’t she?” said Susan. “It will be a help.”

“Yes, it will be a little help,” said Hetta. “But we have done very well hitherto without winter lodgers.”

“But uncle Bell said she was to.”

“What is uncle Bell to us?” said Hetta, who had a spirit of her own. And she began to surmise within herself whether Aaron Dunn would join the Baptist congregation, and whether Phineas Beckard would approve of this new move.

“He is a very well-behaved young man at any rate,” said Susan, “and he draws beautifully. Did you see those things he was doing?”

“He draws very well, I dare say,” said Hetta, who regarded this as but a poor warranty for good behaviour. Hetta also had some fear of wolves–not for herself perhaps; but for her sister.

Aaron Dunn’s work–the commencement of his work–lay at some distance from the Springs, and he left every morning with a lot of workmen by an early train–almost before daylight. And every morning, cold and wintry as the mornings were, the widow got him his breakfast with her own hands. She took his dollars and would not leave him altogether to the awkward mercies of Kate O’Brien; nor would she trust her girls to attend upon the young man. Hetta she might have trusted; but then Susan would have asked why she was spared her share of such hardship.

In the evening, leaving his work when it was dark, Aaron always returned, and then the evening was passed together. But they were passed with the most demure propriety. These women would make the tea, cut the bread and butter, and then sew; while Aaron Dunn, when the cups were removed, would always go to his plans and drawings.

On Sundays they were more together; but even on this day there was cause of separation, for Aaron went to the Episcopalian church, rather to the disgust of Hetta. In the afternoon, however, they were together; and then Phineas Beckard came in to tea on Sundays, and he and Aaron got to talking on religion; and though they disagreed pretty much, and would not give an inch either one or the other, nevertheless the minister told the widow, and Hetta too probably, that the lad had good stuff in him, though he was so stiff-necked.

“But he should be more modest in talking on such matters with a minister,” said Hetta.

The Rev. Phineas acknowledged that perhaps he should; but he was honest enough to repeat that the lad had stuff in him. “Perhaps after all he is not a wolf,” said the widow to herself.

Things went on in this way for above a month. Aaron had declared to himself over and over again that that face was sweet to look upon, and had unconsciously promised to himself certain delights in talking and perhaps walking with the owner of it. But the walkings had not been achieved–nor even the talkings as yet. The truth was that Dunn was bashful with young women, though he could be so stiff- necked with the minister.

And then he felt angry with himself, inasmuch as he had advanced no further; and as he lay in his bed–which perhaps those pretty hands had helped to make–he resolved that he would be a thought bolder in his bearing. He had no idea of making love to Susan Bell; of course not. But why should he not amuse himself by talking to a pretty girl when she sat so near him, evening after evening?

“What a very quiet young man he is,” said Susan to her sister.

“He has his bread to earn, and sticks to his work,” said Hetta. “No doubt he has his amusement when he is in the city,” added the elder sister, not wishing to leave too strong an impression of the young man’s virtue.

They had all now their settled places in the parlour. Hetta sat on one side of the fire, close to the table, having that side to herself. There she sat always busy. She must have made every dress and bit of linen worn in the house, and hemmed every sheet and towel, so busy was she always. Sometimes, once in a week or so, Phineas Beckard would come in, and then place was made for him between Hetta’s usual seat and the table. For when there he would read out loud. On the other side, close also to the table, sat the widow, busy, but not savagely busy as her elder daughter. Between Mrs. Bell and the wall, with her feet ever on the fender, Susan used to sit; not absolutely idle, but doing work of some slender pretty sort, and talking ever and anon to her mother. Opposite to them all, at the other side of the table, far away from the fire, would Aaron Dunn place himself with his plans and drawings before him.

“Are you a judge of bridges, ma’am?” said Aaron, the evening after he had made his resolution. ‘Twas thus he began his courtship.

“Of bridges?” said Mrs. Bell–“oh dear no, sir.” But she put out her hand to take the little drawing which Aaron handed to her.

“Because that’s one I’ve planned for our bit of a new branch from Moreau up to Lake George. I guess Miss Susan knows something about bridges.”

“I guess I don’t,” said Susan–“only that they oughtn’t to tumble down when the frost comes.”

“Ha, ha, ha; no more they ought. I’ll tell McEvoy that.” McEvoy had been a former engineer on the line. “Well, that won’t burst with any frost, I guess.”

“Oh my! how pretty!” said the widow, and then Susan of course jumped up to look over her mother’s shoulder.

The artful dodger! he had drawn and coloured a beautiful little sketch of a bridge; not an engineer’s plan with sections and measurements, vexatious to a woman’s eye, but a graceful little bridge with a string of cars running under it. You could almost hear the bell going.

“Well; that is a pretty bridge,” said Susan. “Isn’t it, Hetta?”

“I don’t know anything about bridges,” said Hetta, to whose clever eyes the dodge was quite apparent. But in spite of her cleverness Mrs. Bell and Susan had soon moved their chairs round to the table, and were looking through the contents of Aaron’s portfolio. “But yet he may be a wolf,” thought the poor widow, just as she was kneeling down to say her prayers.

That evening certainly made a commencement. Though Hetta went on pertinaciously with the body of a new dress, the other two ladies did not put in another stitch that night. From his drawings Aaron got to his instruments, and before bedtime was teaching Susan how to draw parallel lines. Susan found that she had quite an aptitude for parallel lines, and altogether had a good time of it that evening. It is dull to go on week after week, and month after month, talking only to one’s mother and sister. It is dull though one does not oneself recognise it to be so. A little change in such matters is so very pleasant. Susan had not the slightest idea of regarding Aaron as even a possible lover. But young ladies do like the conversation of young gentlemen. Oh, my exceedingly proper prim old lady, you who are so shocked at this as a general doctrine, has it never occurred to you that the Creator has so intended it?

Susan understanding little of the how and why, knew that she had had a good time, and was rather in spirits as she went to bed. But Hetta had been frightened by the dodge.

“Oh, Hetta, you should have looked at those drawings. He is so clever!” said Susan.

“I don’t know that they would have done me much good,” replied Hetta.

“Good! Well, they’d do me more good than a long sermon, I know,” said Susan; “except on a Sunday, of course,” she added apologetically. This was an ill-tempered attack both on Hetta and Hetta’s admirer. But then why had Hetta been so snappish?

“I’m sure he’s a wolf;” thought Hetta as she went to bed.

“What a very clever young man he is!” thought Susan to herself as she pulled the warm clothes round about her shoulders and ears.

“Well that certainly was an improvement,” thought Aaron as he went through the same operation, with a stronger feeling of self- approbation than he had enjoyed for some time past.

In the course of the next fortnight the family arrangements all altered themselves. Unless when Beckard was there Aaron would sit in the widow’s place, the widow would take Susan’s chair, and the two girls would be opposite. And then Dunn would read to them; not sermons, but passages from Shakspeare, and Byron, and Longfellow. “He reads much better than Mr. Beckard,” Susan had said one night. “Of course you’re a competent judge!” had been Hetta’s retort. “I mean that I like it better,” said Susan. “It’s well that all people don’t think alike,” replied Hetta.

And then there was a deal of talking. The widow herself, as unconscious in this respect as her youngest daughter, certainly did find that a little variety was agreeable on those long winter nights; and talked herself with unaccustomed freedom. And Beckard came there oftener and talked very much. When he was there the two young men did all the talking, and they pounded each other immensely. But still there grew up a sort of friendship between them.

“Mr. Beckard seems quite to take to him,” said Mrs. Bell to her eldest daughter.

“It is his great good nature, mother,” replied Hetta.

It was at the end of the second month when Aaron took another step in advance–a perilous step. Sometimes on evenings he still went on with his drawing for an hour or so; but during three or four evenings he never asked any one to look at what he was doing. On one Friday he sat over his work till late, without any reading or talking at all; so late that at last Mrs. Bell said, “If you’re going to sit much longer, Mr. Dunn, I’ll get you to put out the candles.” Thereby showing, had he known it or had she, that the mother’s confidence in the young man was growing fast. Hetta knew all about it, and dreaded that the growth was too quick.

“I’ve finished now,” said Aaron; and he looked carefully at the cardboard on which he had been washing in his water-colours. “I’ve finished now.” He then hesitated a moment; but ultimately he put the card into his portfolio and carried it up to his bedroom. Who does not perceive that it was intended as a present to Susan Bell?

The question which Aaron asked himself that night, and which he hardly knew how to answer, was this. Should he offer the drawing to Susan in the presence of her mother and sister, or on some occasion when they two might be alone together? No such occasion had ever yet occurred, but Aaron thought that it might probably be brought about. But then he wanted to make no fuss about it. His first intention had been to chuck the drawing lightly across the table when it was completed, and so make nothing of it. But he had finished it with more care than he had at first intended; and then he had hesitated when he had finished it. It was too late now for that plan of chucking it over the table.

On the Saturday evening when he came down from his room, Mr. Beckard was there, and there was no opportunity that night. On the Sunday, in conformity with a previous engagement, he went to hear Mr. Beckard preach, and walked to and from meeting with the family. This pleased Mrs. Bell, and they were all very gracious that afternoon. But Sunday was no day for the picture.

On Monday the thing had become of importance to him. Things always do when they are kept over. Before tea that evening when he came down Mrs. Bell and Susan only were in the room. He knew Hetta for his foe, and therefore determined to use this occasion.

“Miss Susan,” he said, stammering somewhat, and blushing too, poor fool! “I have done a little drawing which I want you to accept,” and he put his portfolio down on the table.

“Oh! I don’t know,” said Susan, who had seen the blush.

Mrs. Bell had seen the blush also, and pursed her mouth up, and looked grave. Had there been no stammering and no blush, she might have thought nothing of it.

Aaron saw at once that his little gift was not to go down smoothly. He was, however, in for it now, so he picked it out from among the other papers in the case and brought it over to Susan. He endeavoured to hand it to her with an air of indifference, but I cannot say that he succeeded.

It was a very pretty, well-finished, water-coloured drawing, representing still the same bridge, but with more adjuncts. In Susan’s eyes it was a work of high art. Of pictures probably she had seen but little, and her liking for the artist no doubt added to her admiration. But the more she admired it and wished for it, the stronger was her feeling that she ought not to take it.

Poor Susan! she stood for a minute looking at the drawing, but she said nothing; not even a word of praise. She felt that she was red in the face, and uncourteous to their lodger; but her mother was looking at her and she did not know how to behave herself.

Mrs. Bell put out her hand for the sketch, trying to bethink herself as she did so in what least uncivil way she could refuse the present. She took a moment to look at it collecting her thoughts, and as she did so her woman’s wit came to her aid.

“Oh dear, Mr. Dunn, it is very pretty; quite a beautiful picture. I cannot let Susan rob you of that. You must keep that for some of your own particular friends.”

“But I did it for her,” said Aaron innocently.

Susan looked down at the ground, half pleased at the declaration. The drawing would look very pretty in a small gilt frame put over her dressing-table. But the matter now was altogether in her mother’s hands.

“I am afraid it is too valuable, sir, for Susan to accept.”

“It is not valuable at all,” said Aaron, declining to take it back from the widow’s hand.

“Oh, I am quite sure it is. It is worth ten dollars at least–or twenty,” said poor Mrs. Bell, not in the very best taste. But she was perplexed, and did not know how to get out of the scrape. The article in question now lay upon the table-cloth, appropriated by no one, and at this moment Hetta came into the room.

“It is not worth ten cents,” said Aaron, with something like a frown on his brow. “But as we had been talking about the bridge, I thought Miss Susan would accept it.”

“Accept what?” said Hetta. And then her eye fell upon the drawing and she took it up.

“It is beautifully done,” said Mrs. Bell, wishing much to soften the matter; perhaps the more so that Hetta the demure was now present. “I am telling Mr. Dunn that we can’t take a present of anything so valuable.”

“Oh dear no,” said Hetta. “It wouldn’t be right.”

It was a cold frosty evening in March, and the fire was burning brightly on the hearth. Aaron Dunn took up the drawing quietly– very quietly–and rolling it up, as such drawings are rolled, put it between the blazing logs. It was the work of four evenings, and his chef-d’oeuvre in the way of art.

Susan, when she saw what he had done, burst out into tears. The widow could very readily have done so also, but she was able to refrain herself, and merely exclaimed–“Oh, Mr. Dunn!”

“If Mr. Dunn chooses to burn his own picture, he has certainly a right to do so,” said Hetta.

Aaron immediately felt ashamed of what he had done; and he also could have cried, but for his manliness. He walked away to one of the parlour-windows, and looked out upon the frosty night. It was dark, but the stars were bright, and he thought that he should like to be walking fast by himself along the line of rails towards Balston. There he stood, perhaps for three minutes. He thought it would be proper to give Susan time to recover from her tears.

“Will you please to come to your tea, sir?” said the soft voice of Mrs. Bell.

He turned round to do so, and found that Susan was gone. It was not quite in her power to recover from her tears in three minutes. And then the drawing had been so beautiful! It had been done expressly for her too! And there had been something, she knew not what, in his eye as he had so declared. She had watched him intently over those four evenings’ work, wondering why he did not show it, till her feminine curiosity had become rather strong. It was something very particular, she was sure, and she had learned that all that precious work had been for her. Now all that precious work was destroyed. How was it possible that she should not cry for more than three minutes?

The others took their meal in perfect silence, and when it was over the two women sat down to their work. Aaron had a book which he pretended to read, but instead of reading he was bethinking himself that he had behaved badly. What right had he to throw them all into such confusion by indulging in his passion? He was ashamed of what he had done, and fancied that Susan would hate him. Fancying that, he began to find at the same time that he by no means hated her.

At last Hetta got up and left the room. She knew that her sister was sitting alone in the cold, and Hetta was affectionate. Susan had not been in fault, and therefore Hetta went up to console her.

“Mrs. Bell,” said Aaron, as soon as the door was closed, “I beg your pardon for what I did just now.”

“Oh, sir, I’m so sorry that the picture is burnt,” said poor Mrs. Bell.

“The picture does not matter a straw,” said Aaron. “But I see that I have disturbed you all,–and I am afraid I have made Miss Susan unhappy.”

“She was grieved because your picture was burnt,” said Mrs. Bell, putting some emphasis on the “your,” intending to show that her daughter had not regarded the drawing as her own. But the emphasis bore another meaning; and so the widow perceived as soon as she had spoken.

“Oh, I can do twenty more of the same if anybody wanted them,” said Aaron. “If I do another like it, will you let her take it, Mrs. Bell?–just to show that you have forgiven me, and that we are friends as we were before?”

Was he, or was he not a wolf? That was the question which Mrs. Bell scarcely knew how to answer. Hetta had given her voice, saying he was lupine. Mr. Beckard’s opinion she had not liked to ask directly. Mr. Beckard she thought would probably propose to Hetta; but as yet he had not done so. And, as he was still a stranger in the family, she did not like in any way to compromise Susan’s name. Indirectly she had asked the question, and, indirectly also, Mr. Beckard’s answer had been favourable.

“But it mustn’t mean anything, sir,” was the widow’s weak answer, when she had paused on the question for a moment.

“Oh no, of course not,” said Aaron, joyously, and his face became radiant and happy. “And I do beg your pardon for burning it; and the young ladies’ pardon too.” And then he rapidly got out his cardboard, and set himself to work about another bridge. The widow, meditating many things in her heart, commenced the hemming of a handkerchief.

In about an hour the two girls came back to the room and silently took their accustomed places. Aaron hardly looked up, but went on diligently with his drawing. This bridge should be a better bridge than that other. Its acceptance was now assured. Of course it was to mean nothing. That was a matter of course. So he worked away diligently, and said nothing to anybody.

When they went off to bed the two girls went into the mother’s room. “Oh, mother, I hope he is not very angry,” said Susan.

“Angry!” said Hetta, “if anybody should be angry, it is mother. He ought to have known that Susan could not accept it. He should never have offered it.”

“But he’s doing another,” said Mrs. Bell.

“Not for her,” said Hetta.

“Yes he is,” said Mrs. Bell, “and I have promised that she shall take it.” Susan as she heard this sank gently into the chair behind her, and her eyes became full of tears. The intimation was almost too much for her.

“Oh, mother!” said Hetta.

“But I particularly said that it was to mean nothing.”

“Oh, mother, that makes it worse.”

Why should Hetta interfere in this way, thought Susan to herself. Had she interfered when Mr. Beckard gave Hetta a testament bound in Morocco? had not she smiled, and looked gratified, and kissed her sister, and declared that Phineas Beckard was a nice dear man, and by far the most elegant preacher at the Springs? Why should Hetta be so cruel?

“I don’t see that, my dear,” said the mother. Hetta would not explain before her sister, so they all went to bed.

On the Thursday evening the drawing was finished. Not a word had been said about it, at any rate in his presence, and he had gone on working in silence. “There,” said he, late on the Thursday evening, “I don’t know that it will be any better if I go on daubing for another hour. There, Miss Susan; there’s another bridge. I hope that will neither burst with the frost, nor yet be destroyed by fire,” and he gave it a light flip with his fingers and sent it skimming over the table.

Susan blushed and smiled, and took it up. “Oh, it is beautiful,” she said. “Isn’t it beautifully done, mother?” and then all the three got up to look at it, and all confessed that it was excellently done.

“And I am sure we are very much obliged to you,” said Susan after a pause, remembering that she had not yet thanked him.

“Oh, it’s nothing,” said he, not quite liking the word “we.” On the following day he returned from his work to Saratoga about noon. This he had never done before, and therefore no one expected that he would be seen in the house before the evening. On this occasion, however, he went straight thither, and as chance would have it, both the widow and her elder daughter were out. Susan was there alone in charge of the house.

He walked in and opened the parlour door. There she sat, with her feet on the fender, with her work unheeded on the table behind her, and the picture, Aaron’s drawing, lying on her knees. She was gazing at it intently as he entered, thinking in her young heart that it possessed all the beauties which a picture could possess.

“Oh, Mr. Dunn,” she said, getting up and holding the telltale sketch behind the skirt of her dress.

“Miss Susan, I have come here to tell your mother that I must st