| |

The Captive in the Caucasus | |

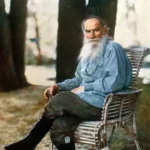

| Author | Leo Tolstoy |

|---|---|

| Published |

1864

|

| Language | English |

| Original Language | Russian |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Genre | Philosophical Fiction, Russian Literature |

1864 Short Story

The Captive in the Caucasus

The Captive in the Caucasus is an English Philosophical Fiction, Russian Literature short story by Russian writer Leo Tolstoy. It was first published in 1864.

The Captive in the Caucasus

by Leo Tolstoy

A gentleman of the name of Zhilin was serving in the Caucasus as an officer. One day he received a letter from home. His aged mother wrote to him: “I am growing old and should like to see my dear little son before I die. Come to me, I pray you, if it be only to bury me, and then in God’s name enter the service again. And I have found for you a nice bride besides; she is sensible, good, and has property. You may fall in love with her perhaps, and you may marry her and be able to retire.”

Zhilin fell a musing: “Yes, indeed, the old lady has been ailing lately, she might never live to see me. Yes, I’ll go, and if the girl is nice I may marry her into the bargain.”

So he went to his colonel, obtained leave of absence, took leave of his comrades, gave his soldiers four pitchers of vodka to drink his health, and prepared to be off.

There was war in the Caucasus then. The roads were impassable night and day. Scarce any of the Russians Could go in or out of the fortress but the Tatars would kill them or carry them off into the mountains. So it was commanded that twice a week a military escort should proceed from fortress to fortress with the people in the midst of it.

The affair happened in the summer. At dawn of day the baggage-wagons assembled in the fortress, the military escort marched out, and the whole company took the road. Zhilin went on horseback, and his wagon with his things was among the baggage.

The distance to be traversed was twenty miles, but the caravan moved but slowly. Sometimes it was the soldiers who stopped, sometimes a wheel flew off one of the baggage-wagons, or a horse wouldn’t go and then they all had to stop and wait.

The sun had already passed the meridian, and the caravan had only gone half the distance. There was nothing but heat and dust, the sun regularly burned, and there was no shelter to be had. All around nothing but the naked steppe not a village, not a wayside bush.

Zhilin had galloped on in front, he had now stopped, and was waiting for the cavalcade to come up. Then he heard a horn blown in the rear, and knew that they had stopped again. Then thought Zhilin : “Why not go on by oneself without the soldiers? I’ve a good horse beneath me, and if I stumble upon the Tatars I can make a bolt for it. Or shall I not go?”

He stood there considering, and up there came trotting another mounted officer, called Kostuilin, with a musket, and he said:

“Let us go on alone, Zhilin. I can’t stand it any longer, I want some grub; the heat is stifling, and my shirt is regularly sticking to me.”

This Kostuilin, by the way, was a thick, heavy, red-faced man, and the sweat was pouring from him. Zhilin thought for a moment, and then said:

“Is your musket loaded?”

“Yes, it is loaded.”

“Well, we’ll go, but on one condition we must keep together.”

And they cantered on in front along the road. They went through the steppe, and as they chatted together they kept glancing on every side of them. They could see for a great distance around them.

The steppe at last had come to an end, and the way lay towards a ravine between two mountains.

“What are you looking at? Let us go straight on!” said Kostuilin. But Zhilin did not listen to him.

“No,” said he, “you just wait below and I’ll go up and have a look round.”

And he urged his horse to the left up the mountain. The horse beneath Zhilin was a good hunter (he had bought it from the horse-fold while still a foal for a hundred roubles, and had broken it in himself), it carried him up the steep ascent as if on wings. He needed but a single glance around there right in front of them, not a furlong ahead, was a whole heap of Tatars, thirty men at least. He no sooner saw them than he set about turning, but the Tatars had seen him too, and posted after him, drawing their muskets while in full career. Zhilin galloped down the slope as fast as his horse’s legs could carry him, at the same time shouting to Kostuilin :

“Out with the muskets! And you, my bea uty” he was thinking of his horse “you, my beauty, spread yourself out and don’t knock your foot against anything for if you stumble now we’re lost. Let me but get to my musket, and I’m hanged if I surrender.”

But Kostuilin, instead of waiting, bolted off at full speed in the direction of the fortress as soon as he beheld the Tatars. He lashed his horse first on one side and then on the other. Only the strong sweep of her tail was visible in the dust

Zhilin perceived that he was in a bit of a hole. His musket was gone, and with a simple shashka nothing could be done. He drove his horse on in the direction of the Russian soldiers there was just a chance of getting away. He saw that six of them were galloping away to cut him off. He had a good horse under him, but they had still better, and they were racing their hardest to bar his way. He began to hesitate, wanted to turn in another direction, but his horse had lost her head, he couldn’t control her, and she was rushing right upon them. He saw approaching him on a grey horse a Tatar with a red beard. The Tatar uttered a shrill cry, gnashed his teeth, and his musket was all ready.

“Well,” thought Zhilin, “I know what you are, you devils, if you take me alive you’ll put me in a dungeon and whip me. I’ll not be taken alive.”

Zhilin was small of stature, but he was brave. Drawing his shashka, he urged his horse straight upon the red-bearded Tatar, thinking to him self : ” I’ll either ride down his horse or fell him with my shashka.”

But Zhilin never got up to the Tatar horse. They fired upon him from behind with their muskets and attacked his horse. His horse fell to the ground with a crash, and Zhilin was thrown off her back. He tried to rise, but two strong-smelling Tatars were already sitting upon him and twisting his arms behind his back. He writhed and twisted and threw off the Tatars, but then three more leaped off their horses and sprang upon him, and began beating him about the head with the butt-ends of their muskets. It grew dark before his eyes, and he began to feel faint. Then the Tatars seized him, rifled his saddle-bags, fastened his arms behind his back, tying them with a Tatar knot, and dragged him to the saddle. They snatched off his hat, they pulled off his boots, examined everything, extorted his money and his watch, and ripped up all his clothes. Zhilin glanced at his horse. She, his dearly-beloved comrade, lay just as she had fallen, on her back, with kicking feet which vainly tried to reach the ground. There was a hole in her head, and out of this hole the black blood gushed with a hiss for several yards around the dust was wet

One of the Tatars went to the horse and proceeded to take the saddle from her back. She went on kicking all the time, and he drew forth a knife and cut her windpipe. There was a hissing sound from her throat, she shivered all .over, and the breath of her life was gone.

The Tatars took away the saddle and bridle. The Tatar with the red beard mounted hi s horse and the others put Zhilin up behind him. To prevent him falling off they fastened him by a thong to the Tatar’s belt and led him away into the mountains.

So there sat Zhilin behind the Tatar, and at every moment he was jolted against, and his very nose came in contact with the Tatar’s malodorous back. All that he could see in front of him, indeed, was the sturdy Tatar’s back, his sinewy, shaven neck sticking out all bluish from beneath his hat. Zhilin’s head was all battered, and the blood kept trickling into his eyes. And it was impossible for him to right himself on his horse or wipe away the blood. His arms were twisted so tightly that his very collar-bone was in danger of breaking.

They travelled for a long time from mountain to mountain, crossed a ford, diverged from the road, and entered a ravine.

Zhilin would have liked to have marked the road by which they were taking him, but his eyes were clotted with blood and he couldn’t turn round properly.

It began to grow dark. They crossed yet another river and began to ascend a rocky mountain, and then came a smell of smoke and the barking of dogs!

At last they came to the aul or Tatar village. The Tatars dismounted from their horses and a crowd of Tatar children assembled, who surrounded Zhilin, fell a yelling and making merry, and took up stones to cast at him.

The Tatar drove away the children, took Zhilin from his horse, and called a workman. Up came a h atchet-faced Nogaets clad only in a shirt, and as the shirt was torn the whole of his breast was bare. The Tatar gave some orders to him. The workman brought a kolodka, that is to say, two oaken blocks fastened together by iron rings, and in one of the rings a cramping iron and a lock. Then they undid Zhilin’s hands, attached the kolodka to his feet, led him into an outhouse, thrust him into it, and fastened the door. Zhilin fell upon a dung-heap. For a time he lay where he fell, then he fumbled his way in the dark to the softest place he could find, and lay down there.

Zhilin scarcely slept at all during the night. It was the season of short nights. He could see it growing light through a rift in the wall. Zhilin arose, made the rift a little bigger, and looked out.

Through the rift the high road was visible going down the mountain-side, to the right was a Tatar saklyaft, with two villages beside it. A black dog lay upon the threshold, a goat with her kids passed along whisking their tails. He saw a Tatar milkmaid coming down from the mountains in a flowered-belted blouse, trousers and boots, with her head covered by a kaftan, and on her head a large tin kuvshinchik. of water. She walked with curved back and head bent forward, and led by the hand a little closely cropped Tatar boy in a little shirt.

The Tatar girl took the water to the saklya, and out came the Tatar of yesterday evening, with the red beard, in a silken beshmet with slippers on his naked feet and a silver knife in his leather girdle. On his head he wore a lofty, black sheepskin hat, flattened down behind. He came out, stretched himself, and stroked his bountiful red beard. He stayed there for a while, gave some orders to his labourer, and went off somewhither.

Next there passed by two children on horses which they had just watered. The horses’ nozzles were wet. Then some more closely cropped youngsters ran by in nothing but shirts, without hose, and they collected into a group, went to the outhouse, took up a long twig and thrust it through the rift in the walL Zhilin gave such a shout at them that the children screamed in chorus and took to their heels, a gleam of naked little knees was the last that was seen of them.

But Zhilin wanted drink, his throat was parched and dry. ” If only they would come to examine me,” thought he. He listened they were opening the outhouse. The red-bearded Tatar appeared, and with him came another, smaller in stature, a blackish sort of little man. His eyes were bright and black, he was ruddy and had a small cropped beard, his face was merry, he was all smiles. The swarthy man was dressed even better than the other; his silken beshmet was blue and trimmed with galoon, the large dagger in his belt was of silver, his red morocco slippers were also trimmed with silver. Mo reover, thick outer slippers covered the finer inner ones. He wore a lofty hat of white lamb’s-wool.

The red-bearded Tatar came in and there was some conversation, and apparently a dispute began. He lent his elbows on the gate, fingered his hanger, and glanced furtively at Zhilin like a hungry wolf. But the swarthy man he was a quick, lively fellow, who seemed to move upon springs came straight up to Zhilin, sat down on his heels, grinned, showing all his teeth, patted him on the shoulder, and began to jabber something in a peculiar way of his own, blinking his eyes, clicking with his tongue, and saying repeatedly:

“Korosho urus! Korosho urus!”

Zhilin did not understand a word of it, and all he said was:

“I am thirsty, give me a drink of water!”

The swarthy man laughed. “Korosho urus!” he said again ‘babbling away in his own peculiar manner.

Zhilin tried to make them understand by a pantomime with his hands and lips that he wanted something to drink.

The swarthy man understood at last, went out and called :

“Dina! Dina!”

A very thin, slender girl, about thirteen years of age, with a face very like the swarthy man’s, then appeared. Plainly she was the swarthy man’s daughter. She also had black sparklin g eyes and a ruddy complexion. She was dressed in a long blue blouse with white sleeves and without a girdle. The folds, sleeves, and breast of her garment were beautifully trimmed. She also wore trousers and slippers, and the inner slippers were protected by outer slippers with high heels. Round her neck she wore a necklace of Russian poltiniks Her head was uncovered, her hair was black, and in her hair was a ribbon, from which dangled a metallic plaque and a silver rouble.

Her father gave her some orders. She ran out, and returned again immediately with a tin kuvshinchik. She handed the water to Zhilin herself, plumping down on her heels, bending right forward so that her shoulders were lower than her knees. There she sat, staring at Zhilin with wide-open eyes as he drank, just as if he were some wild animal.

Zhilin gave the kuvshinchik back to her, and back she bounded like a wild goat. Even her father couldn’t help laughing. Then he sent her somewhere or other. She took the kuvshinchik, ran off, and came back with some unleavened bread on a little round platter, and again she crouched down, all humped forward, gazing at Zhilin with all her eyes.

Then all the Tatars went out and closed the door behind them.

After a little while the Nogaets came to Zhilin and said:

“Come along, master! come along!”

He also did not know Russian. It was p lain to Zhilin, however, that he was ordering him to come somewhither.

Zhilin followed him, still wearing the kolodka. He limped all the way, to walk was impossible, as he had constantly to twist his foot to one side. So Zhilin followed the Nogaets outside. He saw the Tatar village ten houses, with their mosque which had a tower. Before one house stood three saddled horses. A tiny boy was holding their bridles. All at once the swarthy man came leaping out of his house, and waved his hand to Zhilin to signify to him to approach. The Tatar was smiling, jabbering after his fashion, and quickly disappeared into the house again. Zhilin entered the house. The living-room was a good one, the walls were of smoothly-polished clay. Variegated pillows were piled up against the front Wall, rich carpets hung up at the entrance on each side; arms of various sorts pistols, shashki, all of silver were hanging on the carpets. In one corner was a little stove level with the ground. The earthen floor was as clean as a threshing-floor, the front corner was all covered with felt, on the felt were carpets, and on the carpets soft cushions. And on the carpets, in nothing but their bashmaks sat the Tatars there were five of them, the red-bearded man, the swarthy man, and three guests. Soft bulging cushions had been placed behind the backs of them all, and in front of them, on a small platter, were boltered pancakes, beef distributed in little cups, and the Tatar beverage buza in a kuvshinchik. They ate with their hands, and all their hands were in the meat

The swarthy man leaped to his feet, and bade Zhilin sit down apart, not on the carpet, but on the bare floor; then he went back to his carpet, and regaled his guests with pancakes and buza. The labourer made Zhilin sit down in the place assigned to him, he himself took off his outer bashmaks, placed them side by side at the door, where the other bashmaks stood, then sat down on the felt nearer to his masters; he watched how they ate, and his mouth watered as he wiped it When the Tatars had eaten the pancakes, a Tatar woman appeared in just the same sort of blouse that the girl had worn, and in trousers also; her head was covered with a cloth.

She took away the meat and the pancakes, and brought round a good washing vessel, and a kuvshin with a very narrow spout The Tatars then began washing their hands, then they folded their arms, squatted down on their knees, belched in every direction, and recited prayers. Then they talked among themselves. Finally, one of the guests turned towards Zhilin, and began to speak in Russian.

“Kazi Mu’hammed took thee,” said he, pointing to the red-bearded Tatar, “and has sold thee to Abdul Murad,” and he indicated the swarthy Tatar. “Abdul Murad is now thy master.”

Zhilin was silent

Then Abdul Murad began to speak, and kept on pointing at Zhilin, and laughed and said, several times, “Soldat urus! Korosho urus!”

The interpreter said :

“He bids thee write a letter home in order that they may send a ransom for thee. As soon as they send the money, thou shalt be set free.”

Zhilin thought for a moment, and then said :

“How much ransom does he require?”

The Tatars talked among themselves, and then the interpreter said:

“Three thousand moneys.”

“No,” said Zhilin, “I cannot pay that”

Abdul started up and began waving his hands, and said something to Zhilin they all thought he understood. The interpreter interpreted, saying:

“How much wilt thou give? “

Zhilin reflected, and then said, “Five hundred roubles.”

At this the Tatars chattered a great deal and all together. Abdul began to screech at the red-bearded Tatar, and got so excited that the spittle trickled from his mouth. The red-bearded Tatar only blinked his eyes and clicked with his tongue.

Then they were silent again, and the interpreter said:

“Thy master thinks a ransom of five hundred roubles too little. He himself paid two hundred roubles for thee. Kazi Muhammed owed him that, and he took thee in discharge of the debt. Three thousand roubles is the least they will let thee go for. And if thou dost not write they will put thee in the dungeon and punish thee with scourging.”

“What am I to do with them? this is even worse than I thought,” said Zhilin to himself. Then he leaped to his feet and said,

“Tell him, thou dog, that if he wants to frighten me, I won’t give him a kopeck, neither will I write at all I have never feared, and I will not fear you now, you dog.”

The interpreter interpreted, and again they all began talking at once.

For a long time they debated, and then the swarthy man leaped to his feet and came to Zhilin.

“Urus ! ” said he, “dzhiget, dzhiget urus!” and then he laughed.

“Dzhiget” in their language signifies “youth.”

Then he said something to the interpreter, and the interpreter said: “Give a thousand roubles!”

Zhilin stood to his guns. “More than five hundred I will not give,” said he. “You may kill me if you like, but you’ll get no more out of me.”

The Tatars fell a talking together again, then they sent out the labourer for someone, and kept looking at the door and at Zhilia Presently the workman came back and brought with him a man stout, barelegged, and cheery-looking, he also had a kolodka fastened to his leg.

Then Zhilin sighed indeed, for he recognised Kostuilin. So they had taken him too then! The Tatars placed them side by side, they began talking to each other, and the Tatars were silent and looked on. Zhilin related how it had fared with him, Kostuilin told him that his horse had sunk under him, that his musket had missed fire, and that that selfsame Abdul had chased and captured him.

Abdul leaped to his feet, pointed at Kostuilin, and said something. The interpreter interpreted that they both of them had now one master, and whichever of them paid up first should be released first.

“Look now,” said he to Zhilin, “thou makest such a to do, but thy comrade takes it quietly; he has written a letter home telling them to send five thousand roubles. Look now! he shall be fed well and shall be respected.”

“My comrade can do as he likes,” said Zhilin, “no doubt he is rich, but I am not rich. What I have said that will I do. You may kill me if you like, but you will get little profit out of that I will not write for more than five hundred roubles.”

They were silent for a while. Suddenly Abdul leaped up and produced a small coffer, took out a pen, a piece of paper and ink, forced them upon Zhilin, tapped him on the shoulder, and, pointing to them, said: “Write !” He had agreed to take five hundred roubles.

“Wait a bit,” said Zhilin to the interpreter; “tell him that he must feed us well, clothe and shoe us decently, and let us be together we shall be happier then and take off the kolodka” He himself then looked at his master and laughed. And his master laughed likewise. He heard the interpreter out, and then said: “I will give you the best of clothing, a Circassian costume and good boots you might be married in them. And I’ll feed you like princes. And if you want to dwell together well, you can dwell in the outhouse. I can’t take off the kolodka you would run away. Only at night can I take it off.” Then he rushed forward and tapped him on the shoulder “Thy good is my good!” said he.

Then Zhilin wrote the letter, and he wrote no address on the letter, so that it should not go. But he thought to himself:

“I’ll run away.”

Then they led away Zhilin and Kostuilin to the outhouse, brought them maize-straw to spread on the ground, water in a kuvshin, bread, two old Circassian costumes, and two pairs of tattered military boots. They had plainly been taken from off the feet of slain soldiers. At night they took off their kolodki and fastened the door.

Kostuilin wrote home once more, and waited for the money to be sent, in utter weariness. The whole day they sat in the outhouse and counted the days it would take the letter to arrive, or else they slept Zhilin, however, knew very well that his letter would not arrive, and he did not write another.

“Where I should like to know,” thought he, ” would my mother be able to scrape together so much money to pay me out? It was as much as she could do to live on what I sent her. If she had to collect five

the floor, and then sat down and looked at Zhilin, and smiling all over, kept pointing at the pitcher.

“Why is she so delighted?” thought Zhilin. Then he took up the pitcher and began to drink He thought it was water, but it was milk. He drank all the milk. “Khorosho!” said he. How rejoiced Dina was then!

“Khorosho, Ivan, Khorosho,” she repeated, and leaping to her feet, she clapped her hands, snatched up the pitcher, and ran off.

And from thenceforth she, every day, brought him some milk privately. Now the Tatars used to make cheese-cakes out of goats’ milk and dried them on their roofs, and these cheese-cakes she also supplied him with secretly. And once, when the master of the house slaughtered a sheep, she brought him a bit of mutton in her sleeve, flung it down before him and ran off.

Occasionally there were heavy storms, and the rain poured down for a whole hour as if out of a bucket, and all the streams grew turbid and overflowed. Where there had been a ford there was then three arshins of water, and the stones were whirled from their places. Streams then flowed everywhere, and there was a distant roar in the mountains. And so when the storm had passed over, the whole village was full of watercourses. After one of these storms Zhilin asked his master to lend him a knife, carved out a little cylinder and a little board, attached a wheel to them, and fastened a puppet at each end of the wheel.

The girls thereupon brought him rags, and he dressed up one of his puppets as a man and the other as a woman, fastened them well in, and placed the wheel in the stream, whereupon the wheel turned and the puppets leaped up and down.

The whole village assembled to look at them. The little boys came, and the little girls and the women, and at last the Tatars themselves, and they clicked their tongues and said: “Aye! Urus! aye, Ivan!”

Now Abdul had some broken Russian watches. He called Zhilin, pointed at these watches, and clicked with his tongue. Zhilin said:

“Give them to me, and I’ll repair them!”

He took them to pieces with the help of his knife, examined them, put them together again, and returned them to their owner. The watches were now going.

Zhilin’s master was greatly delighted at this, and brought him his old beshmet, which was all in rags, and gave it to him to mend. What could Zhilin do but take and mend it and the same night its owner was able to cover himself with it.

From henceforth Zhilin had the reputation of a master-craftsman. The people used now to come to him from distant villages; one sent his matchlock or his pistol to Zhilin to be mended, another sent his watch or clock. His master even gave him various utensils to mend, such as snuffers, gimlets, and other things.

Once one of the Tatars fell ill, and they sent for Zhilin to see him.

“Come and cure him! ” said they.

Now Zhilin knew nothing at all about curing. Nevertheless, he went, looked at the man, and thought: “Who knows, perhaps he may get well by himself!” So he went back to the outhouse, got water and sand, and mixed them both together. Then he whispered something over the water in the Tatar’s presence and gave him the mixture to drink. Fortunately for him the Tatar recovered. Then Zhilin began to stand very high indeed in their opinion. And these Tatars, who had got used to him, used to cry, “Ivan! Ivan!” whenever they wanted him, and all of them treated him as if he were some pet domestic animal.

But the red-bearded Tatar did not like Zhilin. Whenever he saw him he would frown and turn away, even if he didn’t scold him outright. Now these Tatars hail an old chief who did not live in the aul but up in the mountains. The only time when he saw Zhilin was when he came to pray to God in the mosque. He was small in stature, and a white handkerchief was always wound around his turban, his beard and moustaches were clipped short and as white as down, his face was red like a brick and wrinkled. He had the curved nose of a vulture, grey evil eyes, and no teeth, except a couple of fangs. He used to come in his turban, leaning on his crutch, and glaring about him like an old wolf. Whenever he saw Zhilin he began to snarl and turned away.

Once Zhilin went up the mountain to see how the old chief lived. As he went along a little path he

saw a little garden surrounded by a stone fence with wild cherry and peach trees looking over it, and inside a little hut with a flat roof. Zhilin approached nearer, and then he saw beehives made of plaited straw ului they called them and the bees flying about and humming. And the little old man was on his tiny knees doing something to the hives. Zhilin raised himself a little higher to have a better look, and his kolodka grated. The little old man looked round and whined aloud, then he drew a pistol out of his girdle and fired point-blank at Zhilin. After firing he hid behind a stone.

Next morning the old man came down to Zhilin’s master to complain of him. Zhilin’s master called him and said to him with a laugh:

“Why didst thou go to the old man?”

“I did him no harm,” said Zhilin. “I only wanted to see how he lived.”

Zhilin’s master interpreted.

The old man was very angry however. He hissed and gabbled, and his two fangs protruded, and he shook his fist at Zhilin.

Zhilin did not understand it at all. All he understood was that the old man bade his master kill all the Russians and not keep any of them in the aul. Finally, the old man went away.

Zhilin now began to ask his master who the little old man was, and this is what his master told him.

“That is a great man. He was our foremost zhigit and has killed many Russians; he is also rich. Once he had eight sons, and they all dwelt together in one village. The Russians came, destroyed the village, and slew seven of his sons. One son only remained, and he surrendered to the Russians. Then the old man went away, and surrendered himself also to the Russians. He lived with them for three months, found out where his son was, slew him, and ran away. From thenceforth he renounced warfare and went to Mecca to pray to God. Hence he has his turban. Whoever has been to Mecca is called Hadji, and may put on a turban. He does not love thy brother. He bade me slay thee, but I will not slay thee, because I want to make money out of thee; and, besides, I have begun to love thee, Ivan, and so far from killing thee, I would not let thee go away at all if I hadn’t given my word upon it.” He laughed, and then he added in Russian: “The welfare of thee, Ivan, is the welfare of me, Abdul!”

So Zhilin lived like this for a month. In the daytime he went about the aul, or made all sorts of things with his hands, and when night came, and all was silent in the aul, he began digging inside his outhouse. Digging was difficult because of the rock, but he fretted away the rock with a file, and dug a hole under the wall, through which, at the proper time, he meant to crawl.

“If only I knew the place fairly well,” he said to himself, “if only I knew in which direction to go. But the Tatars never give themselves away.”

One day he chose a time when his master had gone away, and after dinner he went up the mountain behind the aul he wanted to survey the whole place from thence. But when his master went away he had commanded a lad to follow Zhilin wherever he went and not lose sight of him. So the youngster ran after Zhilin, and cried: “Don’t go! Father didn’t tell you to. I’ll call the people this instant.”

Zhilin set about persuading him.

“I’m not going far,” said he, “I only want to climb that mountain there. I want to find herbs to cure your people. Come with me! I can’t run away with this kolodka on my leg. And to-morrow I’ll make you a bow and arrows.”

So he persuaded the lad and they went together. The mountain did not seem far, but it was difficult going with the kolodka; he went on and on and it taxed his utmost strength. Wheh he got to the summit Zhilin sat down to take a good look at the place. To the south, behind the outhouse was a gully, a tabun was roaming along there, and another aul was visible as a tiny point. Beyond this aul was another and still steeper mountain, and behind this mountain yet another. Between the mountains was the blue outline of a wood, and there could be seen other mountains,