| |

Jean Gourdon’s Four Days | |

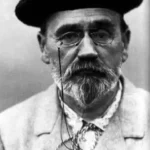

| Author | Emile Zola |

|---|---|

| Published |

1866

|

| Language | English |

| Original Language | French |

| Nationality | French |

| Genre | French Literature, Naturalism |

1866 Short Story

Jean Gourdon’s Four Days

Jean Gourdon’s Four Days is an English French Literature, Naturalism short story by French writer Emile Zola. It was first published in 1866.

Jean Gourdon’s Four Days

by Emile Zola

SPRING

On that particular day, at about five o’clock in the morning, the sun entered with delightful abruptness into the little room I occupied at the house of my uncle Lazare, parish priest of the hamlet of Dourgues. A broad yellow ray fell upon ray closed eyelids, and I awoke in light.

My room, which was whitewashed, and had deal furniture, was full of attractive gaiety. I went to the window and gazed at the Durance, which traced its broad course amidst the dark green verdure of the valley. Fresh puffs of wind caressed my face, and the murmur of the trees and river seemed to call me to them.

I gently opened my door. To get out I had to pass through my uncle’s room. I proceeded on tip-toe, fearing the creaking of my thick boots might awaken the worthy man, who was still slumbering with a smiling countenance. And I trembled at the sound of the church bell tolling the Angelus. For some days past my uncle Lazare had been following me about everywhere, looking sad and annoyed. He would perhaps have prevented me going over there to the edge of the river, and hiding myself among the willows on the bank, so as to watch for Babet passing, that tall dark girl who had come with the spring.

But my uncle was sleeping soundly. I felt something like remorse in deceiving him and running away in this manner. I stayed for an instant and gazed on his calm countenance, with its gentle expression enhanced by rest, and I recalled to mind with feeling the day when he had come to fetch me in the chilly and deserted home which my mother’s funeral was leaving. Since that day, what tenderness, what devotedness, what good advice he had bestowed on me! He had given me his knowledge and his kindness, all his intelligence and all his heart.

I was tempted for a moment to cry out to him:

“Get up, uncle Lazare! let us go for a walk together along that path you are so fond of beside the Durance. You will enjoy the fresh air and morning sun. You will see what an appetite you will have on your return!”

And Babet, who was going down to the river in her light morning gown, and whom I should not be able to see! My uncle would be there, and I would have to lower my eyes. It must be so nice under the willows, lying flat on one’s stomach, in the fine grass! I felt a languid feeling creeping over me, and, slowly, taking short steps, holding my breath, I reached the door. I went downstairs, and began running like a madcap in the delightful, warm May morning air.

The sky was quite white on the horizon, with exquisitely delicate blue and pink tints. The pale sun seemed like a great silver lamp, casting a shower of bright rays into the Durance. And the broad, sluggish river, expanding lazily over the red sand, extended from one end of the valley to the other, like a stream of liquid metal. To the west, a line of low rugged hills threw slight violet streaks on the pale sky.

I had been living in this out-of-the-way corner for ten years. How often had I kept my uncle Lazare waiting to give me my Latin lesson! The worthy man wanted to make me learned. But I was on the other side of the Durance, ferreting out magpies, discovering a hill which I had not yet climbed. Then, on my return, there were remonstrances: the Latin was forgotten, my poor uncle scolded me for having torn my trousers, and he shuddered when he noticed sometimes that the skin underneath was cut. The valley was mine, really mine; I had conquered it with my legs, and I was the real landlord by right of friendship. And that bit of river, those two leagues of the Durance, how I loved them, how well we understood one another when together! I knew all the whims of my dear stream, its anger, its charming ways, its different features at each hour of the day.

When I reached the water’s edge on that particular morning, I felt something like giddiness at seeing it so gentle and so white. It had never looked so gay. I slipped rapidly beneath the willows, to an open space where a broad patch of sunlight fell on the dark grass. There I laid me down on my stomach, listening, watching the pathway by which Babet would come, through the branches.

“Oh! how sound uncle Lazare must be sleeping!” I thought.

And I extended myself at full length on the moss. The sun struck gentle heat into my back, whilst my breast, buried in the grass, was quite cool.

Have you never examined the turf, at close quarters, with your eyes on the blades of grass? Whilst I was waiting for Babet, I pried indiscreetly into a tuft which was really a whole world. In my bunch of grass there were streets, cross roads, public squares, entire cities. At the bottom of it, I distinguished a great dark patch where the shoots of the previous spring were decaying sadly, then slender stalks were growing up, stretching out, bending into a multitude of elegant forms, and producing frail colonnades, churches, virgin forests. I saw two lean insects wandering in the midst of this immensity; the poor children were certainly lost, for they went from colonnade to colonnade, from street to street, in an affrighted, anxious way.

It was just at this moment that, on raising my eyes, I saw Babet’s white skirts standing out against the dark ground at the top of the pathway. I recognized her printed calico gown, which was grey, with small blue flowers. I sunk down deeper in the grass, I heard my heart thumping against the earth and almost raising me with slight jerks. My breast was burning now, I no longer felt the freshness of the dew.

The young girl came nimbly down the pathway, her skirts skimming the ground with a swinging motion that charmed me, I saw her at full length, quite erect, in her proud and happy gracefulness. She had no idea I was there behind the willows; she walked with a light step, she ran without giving a thought to the wind, which slightly raised her gown. I could distinguish her feet, trotting along quickly, quickly, and a piece of her white stockings, which was perhaps as large as one’s hand, and which made me blush in a manner that was alike sweet and painful.

Oh! then, I saw nothing else, neither the Durance, nor the willows, nor the whiteness of the sky. What cared I for the valley! It was no longer my sweetheart; I was quite indifferent to its joy and its sadness. What cared I for my friends, the stories, and the trees on the hills! The river could run away all at once if it liked; I would not have regretted it.

And the spring, I did not care a bit about the spring! Had it borne away the sun that warmed my back, its leaves, its rays, all its May morning, I should have remained there, in ecstasy, gazing at Babet, running along the pathway, and swinging her skirts deliciously. For Babet had taken the valley’s place in my heart, Babet was the spring, I had never spoken to her. Both of us blushed when we met one another in my uncle Lazare’s church. I could have vowed she detested me.

She talked on that particular day for a few minutes with the women who were washing. The sound of her pearly laughter reached as far as me, mingled with the loud voice of the Durance. Then she stooped down to take a little water in the hollow of her hand; but the bank was high, and Babet, who was on the point of slipping, saved herself by clutching the grass. I gave a frightful shudder, which made my blood run cold. I rose hastily, and, without feeling ashamed, without reddening, ran to the young girl. She cast a startled look at me; then she began to smile. I bent down, at the risk of falling. I succeeded in filling my right hand with water by keeping my fingers close together. And I presented this new sort of cup to Babet’ asking her to drink.

The women who were washing laughed. Babet, confused, did not dare accept; she hesitated, and half turned her head away. At last she made up her mind, and delicately pressed her lips to the tips of my fingers; but she had waited too long, all the water had run away. Then she burst out laughing, she became a child again, and I saw very well that she was making fun of me.

I was very silly. I bent forward again. This time I took the water in both hands and hastened to put them to Babet’s lips. She drank, and I felt the warm kiss from her mouth run up my arms to my breast, which it filled with heat.

“Oh! how my uncle must sleep!” I murmured to myself.

Just as I said that, I perceived a dark shadow beside me, and, having turned round, I saw my uncle Lazare, in person, a few paces away, watching Babet and me as if offended. His cassock appeared quite white in the sun; in his look I saw reproaches which made me feel inclined to cry.

Babet was very much afraid. She turned quite red, and hurried off stammering:

“Thanks, Monsieur Jean, I thank you very much.”

As for me, wiping my wet hands, I stood motionless and confused before my uncle Lazare.

The worthy man, with folded arms, and bringing back a corner of his cassock, watched Babet, who was running up the pathway without turning her head. Then, when she had disappeared behind the hedges, he lowered his eyes to me, and I saw his pleasant countenance smile sadly.

“Jean,” he said to me, “come into the broad walk. Breakfast is not ready. We have half an hour to spare.”

He set out with his rather heavy tread, avoiding the tufts of grass wet with dew. A part of the bottom of his cassock that was dragging along the ground, made a dull crackling sound. He held his breviary under his arm; but he had forgotten his morning lecture, and he advanced dreamily, with bowed head, and without uttering a word.

His silence tormented me. He was generally so talkative. My anxiety increased at each step. He had certainly seen me giving Babet water to drink. What a sight, O Lord! The young girl, laughing and blushing, kissed the tips of my fingers, whilst I, standing on tip-toe, stretching out my arms, was leaning forward as if to kiss her. My action now seemed to me frightfully audacious. And all my timidity returned. I inquired of myself how I could have dared to have my fingers kissed so sweetly.

And my uncle Lazare, who said nothing, who continued walking with short steps in front of me, without giving a single glance at the old trees he loved! He was assuredly preparing a sermon. He was only taking me into the broad walk to scold me at his ease. It would occupy at least an hour: breakfast would get cold, and I would be unable to return to the water’s edge and dream of the warm burns that Babet’s lips had left on my hands.

We were in the broad walk. This walk, which was wide and short, ran beside the river; it was shaded by enormous oak trees, with trunks lacerated by seams, stretching out their great, tall branches. The fine grass spread like a carpet beneath the trees, and the sun, riddling the foliage, embroidered this carpet with a rosaceous pattern in gold. In the distance, all around, extended raw green meadows.

My uncle went to the bottom of the walk, without altering his step and without turning round. Once there, he stopped, and I kept beside him, understanding that the terrible moment had arrived.

The river made a sharp curve; a low parapet at the end of the walk formed a sort of terrace. This vault of shade opened on a valley of light. The country expanded wide before us, for several leagues. The sun was rising in the heavens, where the silvery rays of morning had become transformed into a stream of gold; blinding floods of light ran from the horizon, along the hills, and spread out into the plain with the glare of fire.

After a moment’s silence, my uncle Lazare turned towards me.

“Good heavens, the sermon!” I thought, and I bowed my head. My uncle pointed out the valley to me, with an expansive gesture; then, drawing himself up, he said, slowly:

“Look, Jean, there is the spring. The earth is full of joy, my boy, and I have brought you here, opposite this plain of light, to show you the first smiles of the young season. Observe what brilliancy and sweetness! Warm perfumes rise from the country and pass across our faces like puffs of life.”

He was silent and seemed dreaming. I had raised my head, astonished, breathing at ease. My uncle was not preaching.

“It is a beautiful morning,” he continued, “a morning of youth. Your eighteen summers find full enjoyment amidst this verdure which is at most eighteen days old. All is great brightness and perfume, is it not? The broad valley seems to you a delightful place: the river is there to give you its freshness, the trees to lend you their shade, the whole country to speak to you of tenderness, the heavens themselves to kiss those horizons that you are searching with hope and desire. The spring belongs to fellows of your age. It is it that teaches the boys how to give young girls to drink–”

I hung my head again. My uncle Lazare had certainly seen me.

“An old fellow like me,” he continued, “unfortunately knows what trust to place in the charms of spring. I, my poor Jean, I love the Durance because it waters these meadows and gives life to all the valley; I love this young foliage because it proclaims to me the coming of the fruits of summer and autumn; I love this sky because it is good to us, because its warmth hastens the fecundity of the earth. I should have had to tell you this one day or other; I prefer telling it you now, at this early hour. It is spring itself that is giving you the lesson. The earth is a vast workshop wherein there is never a slack season. Observe this flower at our feet; to you it is perfume; to me it is labour, it accomplishes its task by producing its share of life, a little black seed which will work in its turn, next spring. And, now, search the vast horizon. All this joy is but the act of generation. If the country be smiling, it is because it is beginning the everlasting task again. Do you hear it now, breathing hard, full of activity and haste? The leaves sigh, the flowers are in a hurry, the corn grows without pausing; all the plants, all the herbs are quarrelling as to which shall spring up the quickest; and the running water, the river comes to assist in the common labour, and the young sun which rises in the heavens is entrusted with the duty of enlivening the everlasting task of the labourers.”

At this point my uncle made me look him straight in the face. He concluded in these terms:

“Jean, you hear what your friend the spring says to you. He is youth, but he is preparing ripe age; his bright smile is but the gaiety of labour. Summer will be powerful, autumn bountiful, for the spring is singing at this moment, while courageously performing its work.”

I looked very stupid. I understood my uncle Lazare. He was positively preaching me a sermon, in which he told me I was an idle fellow and that the time had come to work.

My uncle appeared as much embarrassed as myself. After having hesitated for some instants he said, slightly stammering:

“Jean, you were wrong not to have come and told me all–as you love Babet and Babet loves you–”

“Babet loves me!” I exclaimed.

My uncle made me an ill-humoured gesture.

“Eh! allow me to speak. I don’t want another avowal. She owned it to me herself.”

“She owned that to you, she owned that to you!”

And I suddenly threw my arms round my uncle Lazare’s neck.

“Oh! how nice that is!” I added. “I had never spoken to her, truly. She told you that at the confessional, didn’t she? I would never have dared ask her if she loved me, and I would never have known anything. Oh! how I thank you!”

My uncle Lazare was quite red. He felt that he had just committed a blunder. He had imagined that this was not my first meeting with the young girl, and here he gave me a certainty, when as yet I only dared dream of a hope. He held his tongue now; it was I who spoke with volubility.

“I understand all,” I continued. “You are right, I must work to win Babet. But you will see how courageous I shall be. Ah! how good you are, my uncle Lazare, and how well you speak! I understand what the spring says: I, also, will have a powerful summer and an autumn of abundance. One is well placed here, one sees all the valley; I am young like it, I feel youth within me demanding to accomplish its task–”

My uncle calmed me.

“Very good, Jean,” he said to me. “I had long hoped to make a priest of you, and I imparted to you my knowledge with that sole aim. But what I saw this morning at the waterside compels me to definitely give up my fondest hope. It is Heaven that disposes of us. You will love the Almighty in another way. You cannot now remain in this village, and I only wish you to return when ripened by age and work. I have chosen the trade of printer for you; your education will serve you. One of my friends, who is a printer at Grenoble, is expecting you next Monday.”

I felt anxious.

“And I shall come back and marry Babet?” I inquired.

My uncle smiled imperceptibly; and, without answering in a direct manner, said:

“The remainder is the will of Heaven.”

“You are heaven, and I have faith in your kindness. Oh! uncle, see that Babet does not forget me. I will work for her.”

Then my uncle Lazare again pointed out to me the valley which the warm golden light was overspreading more and more.

“There is hope,” he said to me. “Do not be as old as I am, Jean. Forget my sermon, be as ignorant as this land. It does not trouble about the autumn; it is all engrossed with the joy of its smile; it labours, courageously and without a care. It hopes.”

And we returned to the parsonage, strolling along slowly in the grass, which was scorched by the sun, and chatting with concern of our approaching separation.

Breakfast was cold, as I had foreseen; but that did not trouble me much. I had tears in my eyes each time I looked at my uncle Lazare. And, at the thought of Babet, my heart beat fit to choke me.

I do not remember what I did during the remainder of the day. I think I went and lay down under the willows at the riverside. My uncle was right, the earth was at work. On placing my ear to the grass I seemed to hear continual sounds. Then I dreamed of what my life would be. Buried in the grass until nightfall, I arranged an existence full of labour divided between Babet and my uncle Lazare. The energetic youthfulness of the soil had penetrated my breast, which I pressed with force against the common mother, and at times I imagined myself to be one of the strong willows that lived around me. In the evening I could not dine. My uncle, no doubt, understood the thoughts that were choking me, for he feigned not to notice my want of appetite. As soon as I was able to rise from table, I hastened to return and breathe the open air outside.

A fresh breeze rose from the river, the dull splashing of which I heard in the distance. A soft light fell from the sky. The valley expanded, peaceful and transparent, like a dark shoreless ocean. There were vague sounds in the air, a sort of impassioned tremor, like a great flapping of wings passing above my head. Penetrating perfumes rose with the cool air from the grass.

I had gone out to see Babet; I knew she came to the parsonage every night, and I went and placed myself in ambush behind a hedge. I had got rid of my timidness of the morning; I considered it quite natural to be waiting for her there, because she loved me and I had to tell her of my departure.

“When I perceived her skirts in the limpid night, I advanced noiselessly. Then I murmured in a low voice:

“Babet, Babet, I am here.”

She did not recognise me, at first, and started with fright. When she discovered who it was, she seemed still more frightened, which very much surprised me.

“It’s you, Monsieur Jean,” she said to me. “What are you doing there? What do you want?”

I was beside her and took her hand.

“You love me fondly, do you not?”

“I! who told you that?”

“My uncle Lazare.”

She stood there in confusion. Her hand began to tremble in mine. As she was on the point of running away, I took her other hand. We were face to face, in a sort of hollow in the hedge, and I felt Babet’s panting breath running all warm over my face. The freshness of the air, the rustling silence of the night, hung around us.

“I don’t know,” stammered the young girl, “I never said that–his reverence the cure misunderstood–For mercy’s sake, let me be, I am in a hurry.”

“No, no,” I continued, “I want you to know that I am going away to-morrow, and to promise to love me always.”

“You are leaving to-morrow!”

Oh! that sweet cry, and how tenderly Babet uttered it! I seem still to hear her apprehensive voice full of affliction and love.

“You see,” I exclaimed in my turn, “that my uncle Lazare said the truth. Besides, he never tells fibs. You love me, you love me, Babet! Your lips this morning confided the secret very softly to my fingers.”

And I made her sit down at the foot of the hedge. My memory has retained my first chat of love in its absolute innocence. Babet listened to me like a little sister. She was no longer afraid, she told me the story of her love. And there were solemn sermons, ingenious avowals, projects without end. She vowed she would marry no one but me, I vowed to deserve her hand by labour and tenderness. There was a cricket behind the hedge, who accompanied our chat with his chaunt of hope, and all the valley, whispering in the dark, took pleasure in hearing us talk so softly.

On separating we forgot to kiss each other.

When I returned to my little room, it appeared to me that I had left it for at least a year. That day which was so short, seemed an eternity of happiness. It was the warmest and most sweetly-scented spring-day of my life, and the remembrance of it is now like the distant, faltering voice of my youth.

II

SUMMER

When I awoke at about three o’clock in the morning on that particular day, I was lying on the hard ground tired out, and with my face bathed in perspiration. The hot heavy atmosphere of a July night weighed me down.

My companions were sleeping around me, wrapped in their hooded cloaks; they speckled the grey ground with black, and the obscure plain panted; I fancied I heard the heavy breathing of a slumbering multitude. Indistinct sounds, the neighing of horses, the clash of arms rang out amidst the rustling silence.

The army had halted at about midnight, and we had received orders to lie down and sleep. We had been marching for three days, scorched by the sun and blinded by dust. The enemy were at length in front of us, over there, on those hills on the horizon. At daybreak a decisive battle would be fought.

I had been a victim to despondency. For three days I had been as if trampled on, without energy and without thought for the future. It was the excessive fatigue, indeed, that had just awakened me. Now, lying on my back, with my eyes wide open, I was thinking whilst gazing into the night, I thought of this battle, this butchery, which the sun was about to light up. For more than six years, at the first shot in each fight, I had been saying good-bye to those I loved the most fondly, Babet and uncle Lazare. And now, barely a month before my discharge, I had to say good-bye again, and this time perhaps for ever.

Then my thoughts softened. With closed eyelids I saw Babet and my uncle Lazare. How long it was since I had kissed them! I remembered the day of our separation; my uncle weeping because he was poor, and allowing me to leave like that, and Babet, in the evening, had vowed she would wait for me, and that she would never love another. I had had to quit all, my master at Grenoble, my friends at Dourgues. A few letters had come from time to time to tell me they always loved me, and that happiness was awaiting me in my well-beloved valley. And I, I was going to fight, I was going to get killed.

I began dreaming of my return. I saw my poor old uncle on the threshold of the parsonage extending his trembling arms; and behind him was Babet, quite red, smiling through her tears. I fell into their arms and kissed them, seeking for expressions–

Suddenly the beating of drums recalled me to stern reality. Daybreak had come, the grey plain expanded in the morning mist. The ground became full of life, indistinct forms appeared on all sides; a sound that became louder and louder filled the air; it was the call of bugles, the galloping of horses, the rumble of artillery, the shouting out of orders. War came threatening, amidst my dream of tenderness. I rose with difficulty; it seemed to me that my bones were broken, and that my head was about to split. I hastily got my men together; for I must tell you that I had won the rank of sergeant. We soon received orders to bear to the left and occupy a hillock above the plain.

As we were about to move, the sergeant-major came running along and shouting:

“A letter for Sergeant Gourdon!”

And he handed me a dirty crumpled letter, which had been lying perhaps for a week in the leather bags of the post-office. I had only just time to recognise the writing of my uncle Lazare.

“Forward, march!” shouted the major.

I had to march. For a few seconds I held the poor letter in my hand, devouring it with my eyes; it burnt my fingers; I would have given everything in the world to have sat down and wept at ease whilst reading it. I had to content myself with slipping it under my tunic against my heart.

I have never experienced such agony. By way of consolation I said to myself what my uncle had so often repeated to me: I was in the summer of my life, at the moment of the fierce struggle, and it was essential that I should perform my duty bravely, if I would have a peaceful and bountiful autumn. But these reasons exasperated me the more: this letter, which had come to speak to me of happiness, burnt my heart, which had revolted against the folly of war. And I could not even read it! I was perhaps going to die without knowing what it contained, without perusing my uncle Lazare’s affectionate remarks for the last time.

We had reached the top of the hill. We were to await orders there to advance. The battle-field had been marvellously chosen to slaughter one another at ease. The immense plain expanded for several leagues, and was quite bare, without a house or tree. Hedges and bushes made slight spots on the whiteness of the ground. I have never since seen such a country, an ocean of dust, a chalky soil, bursting open here and there, and displaying its tawny bowels. And never either have I since witnessed a sky of such intense purity, a July day so lovely and so warm; at eight o’clock the sultry heat was already scorching our faces. O the splendid morning, and what a sterile plain to kill and die in!

Firing had broken out with irregular crackling sounds, a long time since, supported by the solemn growl of the cannon. The enemy, Austrians dressed in white, had quitted the heights, and the plain was studded with long files of men, who looked to me about as big as insects. One might have thought it was an ant-hill in insurrection. Clouds of smoke hung over the battle-field. At times, when these clouds broke asunder, I perceived soldiers in flight, smitten with terrified panic. Thus there were currents of fright which bore men away, and outbursts of shame and courage which brought them back under fire.

I could neither hear the cries of the wounded, nor see the blood flow. I could only distinguish the dead which the battalions left behind them, and which resembled black patches. I began to watch the movements of the troops with curiosity, irritated at the smoke which hid a good half of the show, experiencing a sort of egotistic pleasure at the knowledge that I was in security, whilst others were dying.

At about nine o’clock we were ordered to advance. We went down the hill at the double and proceeded towards the centre which was giving way. The regular beat of our footsteps appeared to me funeral-like. The bravest among us panting, pale and with haggard features.

I have made up my mind to tell the truth. At the first whistle of the bullets, the battalion suddenly came to a halt, tempted to fly.

“Forward, forward!” shouted the chiefs.

But we were riveted to the ground, bowing our heads when a bullet whistled by our ears. This movement is instinctive; if shame had not restrained me, I would have thrown myself flat on my stomach in the dust.

“Before us was a huge veil of smoke which we dared not penetrate. Red flashes passed through this smoke. And, shuddering, we still stood still. But the bullets reached us; soldiers fell with yells. The chiefs shouted louder:

“Forward, forward!”

The rear ranks, which they pushed on, compelled us to march. Then, closing our eyes, we made a fresh dash and entered the smoke.

We were seized with furious rage. When the cry of “Halt!” resounded, we experienced difficulty in coming to a standstill. As soon as one is motionless, fear returns and one feels a wish to run away. Firing commenced. We shot in front of us, without aiming, finding some relief in discharging bullets into the smoke. I remember I pulled my trigger mechanically, with lips firmly set together and eyes wide open; I was no longer afraid, for, to tell the truth, I no longer knew if I existed. The only idea I had in my head, was that I would continue firing until all was over. My companion on the left received a bullet full in the face and fell on me; I brutally pushed him away, wiping my cheek which he had drenched with blood. And I resumed firing.

I still remember having seen our colonel, M. de Montrevert, firm and erect upon his horse, gazing quietly towards the enemy. That man appeared to me immense. He had no rifle to amuse himself with, and his breast was expanded to its full breadth above us. From time to time, he looked down, and exclaimed in a dry voice:

“Close the ranks, close the ranks!”

We closed our ranks like sheep, treading on the dead, stupefied, and continuing firing. Until then, the enemy had only sent us bullets; a dull explosion was heard and a shell carried off five of our men. A battery which must have been opposite us and which we could not see, had just opened fire. The shells struck into the middle of us, almost at one spot, making a sanguinary gap which we closed unceasingly with the obstinacy of ferocious brutes.

“Close the ranks, close the ranks!” the colonel coldly repeated.

We were giving the cannon human flesh. Each time a soldier was struck down, I was taking a step nearer death, I was approaching the spot where the shells were falling heavily, crushing the men whose turn had come to die. The corpses were forming heaps in that place, and soon the shells would strike into nothing more than a mound of mangled flesh; shreds of limbs flew about at each fresh discharge. We could no longer close the ranks.

The soldiers yelled, the chiefs themselves were moved.

“With the bayonet, with the bayonet!”

And amidst a shower of bullets the battalion rushed in fury towards the shells. The veil of smoke was torn asunder; we perceived the enemy’s battery flaming red, which was firing at us from the mouths of all its pieces, on the summit of a hillock. But the dash forward had commenced, the shells stopped the dead only.

I ran beside Colonel Montrevert, whose horse had just been killed, and who was fighting like a simple soldier. Suddenly I was struck down; it seemed to me as if my breast opened and my shoulder was taken away. A frightful wind passed over my face.

And I fell. The colonel fell beside me. I felt myself dying. I thought of those I loved, and fainted whilst searching with a withering hand for my uncle Lazare’s letter.

When I came to myself again I was lying on my side in the dust. I was annihilated by profound stupor. I gazed before me with my eyes wide open without seeing anything; it seemed to me that I had lost my limbs, and that my brain was empty. I did not suffer, for life seemed to have departed from my flesh.

The rays of a hot implacable sun fell upon my face like molten lead. I did not feel it. Life returned to me little by little; my limbs became lighter, my shoulder al