| |

A Lost Opportunity | |

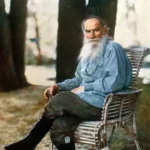

| Author | Leo Tolstoy |

|---|---|

| Published |

1864

|

| Language | English |

| Original Language | Russian |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Genre | Philosophical Fiction, Russian Literature |

1864 Short Story

A Lost Opportunity

A Lost Opportunity is an English Philosophical Fiction, Russian Literature short story by Russian writer Leo Tolstoy. It was first published in 1864.

A Lost Opportunity

by Leo Tolstoy

Then came Peter to Him, and said, Lord, how oft shall my brother sin against me, and I forgive him? till seven times?” . . . . “So likewise shall My heavenly Father do also unto you, if ye from your hearts forgive not every one his brother their trespasses.”–ST. MATTHEW xviii., 21-35.

In a certain village there lived a peasant by the name of Ivan Scherbakoff. He was prosperous, strong, and vigorous, and was considered the hardest worker in the whole village. He had three sons, who supported themselves by their own labor. The eldest was married, the second about to be married, and the youngest took care of the horses and occasionally attended to the plowing.

The peasant’s wife, Ivanovna, was intelligent and industrious, while her daughter-in-law was a simple, quiet soul, but a hard worker.

There was only one idle person in the household, and that was Ivan’s father, a very old man who for seven years had suffered from asthma, and who spent the greater part of his time lying on the brick oven.

Ivan had plenty of everything–three horses, with one colt, a cow with calf, and fifteen sheep. The women made the men’s clothes, and in addition to performing all the necessary household labor, also worked in the field; while the men’s industry was confined altogether to the farm.

What was left of the previous year’s supply of provisions was ample for their needs, and they sold a quantity of oats sufficient to pay their taxes and other expenses.

Thus life went smoothly for Ivan.

The peasant’s next-door neighbor was a son of Gordey Ivanoff, called “Gavryl the Lame.” It once happened that Ivan had a quarrel with him; but while old man Gordey was yet alive, and Ivan’s father was the head of the household, the two peasants lived as good neighbors should. If the women of one house required the use of a sieve or pail, they borrowed it from the inmates of the other house. The same condition of affairs existed between the men. They lived more like one family, the one dividing his possessions with the other, and perfect harmony reigned between the two families.

If a stray calf or cow invaded the garden of one of the farmers, the other willingly drove it away, saying: “Be careful, neighbor, that your stock does not again stray into my garden; we should put a fence up.” In the same way they had no secrets from each other. The doors of their houses and barns had neither bolts nor locks, so sure were they of each other’s honesty. Not a shadow of suspicion darkened their daily intercourse.

Thus lived the old people.

In time the younger members of the two households started farming. It soon became apparent that they would not get along as peacefully as the old people had done, for they began quarrelling without the slightest provocation.

A hen belonging to Ivan’s daughter-in-law commenced laying eggs, which the young woman collected each morning, intending to keep them for the Easter holidays. She made daily visits to the barn, where, under an old wagon, she was sure to find the precious egg.

One day the children frightened the hen and she flew over their neighbor’s fence and laid her egg in their garden.

Ivan’s daughter-in-law heard the hen cackling, but said: “I am very busy just at present, for this is the eve of a holy day, and I must clean and arrange this room. I will go for the egg later on.”

When evening came, and she had finished her task, she went to the barn, and as usual looked under the old wagon, expecting to find an egg. But, alas! no egg was visible in the accustomed place.

Greatly disappointed, she returned to the house and inquired of her mother-in-law and the other members of the family if they had taken it. “No,” they said, “we know nothing of it.”

Taraska, the youngest brother-in-law, coming in soon after, she also inquired of him if he knew anything about the missing egg. “Yes,” he replied; “your pretty, crested hen laid her egg in our neighbors’ garden, and after she had finished cackling she flew back again over the fence.”

The young woman, greatly surprised on hearing this, turned and looked long and seriously at the hen, which was sitting with closed eyes beside the rooster in the chimney-corner. She asked the hen where it laid the egg. At the sound of her voice it simply opened and closed its eyes, but could make no answer.

She then went to the neighbors’ house, where she was met by an old woman, who said: “What do you want, young woman?”

Ivan’s daughter-in-law replied: “You see, babushka [grandmother], my hen flew into your yard this morning. Did she not lay an egg there?”

“We did not see any,” the old woman replied; “we have our own hens–God be praised!–and they have been laying for this long time. We hunt only for the eggs our own hens lay, and have no use for the eggs other people’s hens lay. Another thing I want to tell you, young woman: we do not go into other people’s yards to look for eggs.”

Now this speech greatly angered the young woman, and she replied in the same spirit in which she had been spoken to, only using much stronger language and speaking at greater length.

The neighbor replied in the same angry manner, and finally the women began to abuse each other and call vile names. It happened that old Ivan’s wife, on her way to the well for water, heard the dispute, and joined the others, taking her daughter-in-law’s part.

Gavryl’s housekeeper, hearing the noise, could not resist the temptation to join the rest and to make her voice heard. As soon as she appeared on the scene, she, too, began to abuse her neighbor, reminding her of many disagreeable things which had happened (and many which had not happened) between them. She became so infuriated during her denunciations that she lost all control of herself, and ran around like some mad creature.

Then all the women began to shout at the same time, each trying to say two words to another’s one, and using the vilest language in the quarreller’s vocabulary.

“You are such and such,” shouted one of the women. “You are a thief, a schlukha [a mean, dirty, low creature]; your father-in-law is even now starving, and you have no shame. You beggar, you borrowed my sieve and broke it. You made a large hole in it, and did not buy me another.”

“You have our scale-beam,” cried another woman, “and must give it back to me;” whereupon she seized the scale-beam and tried to remove it from the shoulders of Ivan’s wife.

In the melee which followed they upset the pails of water. They tore the covering from each other’s head, and a general fight ensued.

Gavryl’s wife had by this time joined in the fracas, and he, crossing the field and seeing the trouble, came to her rescue.

Ivan and his son, seeing that their womenfolk were being badly used, jumped into the midst of the fray, and a fearful fight followed.

Ivan was the most powerful peasant in all the country round, and it did not take him long to disperse the crowd, for they flew in all directions. During the progress of the fight Ivan tore out a large quantity of Gavryl’s beard.

By this time a large crowd of peasants had collected, and it was with the greatest difficulty that they persuaded the two families to stop quarrelling.

This was the beginning.

Gavryl took the portion of his beard which Ivan had torn out, and, wrapping it in a paper, went to the volostnoye (moujiks’ court) and entered a complaint against Ivan.

Holding up the hair, he said, “I did not grow this for that bear Ivan to tear out!”

Gavryl’s wife went round among the neighbors, telling them that they must not repeat what she told them, but that she and her husband were going to get the best of Ivan, and that he was to be sent to Siberia.

And so the quarrelling went on.

The poor old grandfather, sick with asthma and lying on the brick oven all the time, tried from the first to dissuade them from quarrelling, and begged of them to live in peace; but they would not listen to his good advice. He said to them: “You children are making a great fuss and much trouble about nothing. I beg of you to stop and think of what a little thing has caused all this trouble. It has arisen from only one egg. If our neighbors’ children picked it up, it is all right. God bless them! One egg is of but little value, and without it God will supply sufficient for all our needs.”

Ivan’s daughter-in-law here interposed and said, “But they called us vile names.”

The old grandfather again spoke, saying: “Well, even if they did call you bad names, it would have been better to return good for evil, and by your example show them how to speak better. Such conduct on your part would have been best for all concerned.” He continued: “Well, you had a fight, you wicked people. Such things sometimes happen, but it would be better if you went afterward and asked forgiveness and buried your grievances out of sight. Scatter them to the four winds of heaven, for if you do not do so it will be the worse for you in the end.”

The younger members of the family, still obstinate, refused to profit by the old man’s advice, and declared he was not right, and that he only liked to grumble in his old-fashioned way.

Ivan refused to go to his neighbor, as the grandfather wished, saying: “I did not tear out Gavryl’s beard. He did it himself, and his son tore my shirt and trousers into shreds.”

Ivan entered suit against Gavryl. He first went to the village justice, and not getting satisfaction from him he carried his case to the village court.

While the neighbors were wrangling over the affair, each suing the other, it happened that a perch-bolt from Gavryl’s wagon was lost; and the women of Gavryl’s household accused Ivan’s son of stealing it.

They said: “We saw him in the night-time pass by our window, on his way to where the wagon was standing.” “And my kumushka [sponsor],” said one of them, “told me that Ivan’s son had offered it for sale at the kabak [tavern].”

This accusation caused them again to go into court for a settlement of their grievances.

While the heads of the families were trying to have their troubles settled in court, their home quarrels were constant, and frequently resulted in hand-to-hand encounters. Even the little children followed the example of their elders and quarrelled incessantly.

The women, when they met on the riverbank to do the family washing, instead of attending to their work passed the time in abusing each other, and not infrequently they came to blows.

At first the male members of the families were content with accusing each other of various crimes, such as stealing and like meannesses. But the trouble in this mild form did not last long.

They soon resorted to other measures. They began to appropriate one another’s things without asking permission, while various articles disappeared from both houses and could not be found. This was done out of revenge.

This example being set by the men, the women and children also followed, and life soon became a burden to all who took part in the strife.

Ivan Scherbakoff and “Gavryl the Lame” at last laid their trouble before the mir (village meeting), in addition to having been in court and calling on the justice of the peace. Both of the latter had grown tired of them and their incessant wrangling. One time Gavryl would succeed in having Ivan fined, and if he was not able to pay it he would be locked up in the cold dreary prison for days. Then it would be Ivan’s turn to get Gavryl punished in like manner, and the greater the injury the one could do the other the more delight he took in it.

The success of either in having the other punished only served to increase their rage against each other, until they were like mad dogs in their warfare.

If anything went wrong with one of them he immediately accused his adversary of conspiring to ruin him, and sought revenge without stopping to inquire into the rights of the case.

When the peasants went into court, and had each other fined and imprisoned, it did not soften their hearts in the least. They would only taunt one another on such occasions, saying: “Never mind; I will repay you for all this.”

This state of affairs lasted for six years.

Ivan’s father, the sick old man, constantly repeated his good advice. He would try to arouse their conscience by saying: “What are you doing, my children? Can you not throw off all these troubles, pay more attention to your business, and suppress your anger against your neighbors? There is no use in your continuing to live in this way, for the more enraged you become against each other the worse it is for you.”

Again was the wise advice of the old man rejected.

At the beginning of the seventh year of the existence of the feud it happened that a daughter-in-law of Ivan’s was present at a marriage. At the wedding feast she openly accused Gavryl of stealing a horse. Gavryl was intoxicated at the time and was in no mood to stand the insult, so in retaliation he struck the woman a terrific blow, which confined her to her bed for more than a week. The woman being in delicate health, the worst results were feared.

Ivan, glad of a fresh opportunity to harass his neighbor, lodged a formal complaint before the district-attorney, hoping to rid himself forever of Gavryl by having him sent to Siberia.

On examining the complaint the district-attorney would not consider it, as by that time the injured woman was walking about and as well as ever.

Thus again Ivan was disappointed in obtaining his revenge, and, not being satisfied with the district-attorney’s decision, had the case transferred to the court, where he used all possible means to push his suit. To secure the favor of the starshina (village mayor) he made him a present of half a gallon of sweet vodki; and to the mayor’s pisar (secretary) also he gave presents. By this means he succeeded in securing a verdict against Gavryl. The sentence was that Gavryl was to receive twenty lashes on his bare back, and the punishment was to be administered in the yard which surrounded the court-house.

When Ivan heard the sentence read he looked triumphantly at Gavryl to see what effect it would produce on him. Gavryl turned very white on hearing that he was to be treated with such indignity, and turning his back on the assembly left the room without uttering a word.

Ivan followed him out, and as he reached his horse he heard Gavryl saying: “Very well; my spine will burn from the lashes, but something will burn with greater fierceness in Ivan’s household before long.”

Ivan, on hearing these words, instantly returned to the court, and going up to the judges said: “Oh! just judges, he threatens to burn my house and all it contains.”

A messenger was immediately sent in search of Gavryl, who was soon found and again brought into the presence of the judges.

“Is it true,” they asked, “that you said you would burn Ivan’s house and all it contained?”

Gavryl replied: “I did not say anything of the kind. You may give me as many lashes as you please–that is, if you have the power to do so. It seems to me that I alone have to suffer for the truth, while he,” pointing to Ivan, “is allowed to do and say what he pleases.” Gavryl wished to say something more, but his lips trembled, and the words refused to come; so in silence he turned his face toward the wall.

The sight of so much suffering moved even the judges to pity, and, becoming alarmed at Gavryl’s continued silence, they said, “He may do both his neighbor and himself some frightful injury.”

“See here, my brothers,” said one feeble old judge, looking at Ivan and Gavryl as he spoke, “I think you had better try to arrange this matter peaceably. You, brother Gavryl, did wrong to strike a woman who was in delicate health. It was a lucky thing for you that God had mercy on you and that the woman did not die, for if she had I know not what dire misfortune might have overtaken you! It will not do either of you any good to go on living as you are at present. Go, Gavryl, and make friends with Ivan; I am sure he will forgive you, and we will set aside the verdict just given.”

The secretary on hearing this said: “It is impossible to do this on the present case. According to Article 117 this matter has gone too far to be settled peaceably now, as the verdict has been rendered and must be enforced.”

But the judges would not listen to the secretary, saying to him: “You talk altogether too much. You must remember that the first thing is to fulfill God’s command to ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself,’ and all will be well with you.”

Thus with kind words the judges tried to reconcile the two peasants. Their words fell on stony ground, however, for Gavryl would not listen to them.

“I am fifty years old,” said Gavryl, “and have a son married, and never from my birth has the lash been applied to my back; but now this bear Ivan has secured a verdict against me which condemns me to receive twenty lashes, and I am forced to bow to this decision and suffer the shame of a public beating. Well, he will have cause to remember this.”

At this Gavryl’s voice trembled and he stopped speaking, and turning his back on the judges took his departure.

It was about ten versts’ distance from the court to the homes of the neighbors, and this Ivan travelled late. The women had already gone out for the cattle. He unharnessed his horse and put everything in its place, and then went into the izba (room), but found no one there.

The men had not yet returned from their work in the field and the women had gone to look for the cattle, so that all about the place was quiet. Going into the room, Ivan seated himself on a wooden bench and soon became lost in thought. He remembered how, when Gavryl first heard the sentence which had been passed upon him, he grew very pale, and turned his face to the wall, all the while remaining silent.

Ivan’s heart ached when he thought of the disgrace which he had been the means of bring- ing upon Gavryl, and he wondered how he would feel if the same sentence had been passed upon him. His thoughts were interrupted by the coughing of his father, who was lying on the oven.

The old man, on seeing Ivan, came down off the oven, and slowly approaching his son seated himself on the bench beside him, looking at him as though ashamed. He continued to cough as he leaned on the table and said, “Well, did they sentence him?”

“Yes, they sentenced him to receive twenty lashes,” replied Ivan.

On hearing this the old man sorrowfully shook his head, and said: “This is very bad, Ivan, and what is the meaning of it all? It is indeed very bad, but not so bad for Gavryl as for yourself. Well, suppose his sentence IS carried out, and he gets the twenty lashes, what will it benefit you?”

“He will not again strike a woman,” Ivan replied.

“What is it he will not do? He does not do anything worse than what you are constantly doing!”

This conversation enraged Ivan, and he shouted: “Well, what did he do? He beat a woman nearly to death, and even now he threatens to burn my house! Must I bow to him for all this?”

The old man sighed deeply as he said: “You, Ivan, are strong and free to go wherever you please, while I have been lying for years on the oven. You think that you know everything and that I do not know anything. No! you are still a child, and as such you cannot see that a kind of madness controls your actions and blinds your sight. The sins of others are ever before you, while you resolutely keep your own behind your back. I know that what Gavryl did was wrong, but if he alone should do wrong there would be no evil in the world. Do you think that all the evil in the world is the work of one man alone? No! it requires two persons to work much evil in the world. You see only the bad in Gavryl’s character, but you are blind to the evil that is in your own nature. If he alone were bad and you good, then there would be no wrong.”

The old man, after a pause, continued: “Who tore Gavryl’s beard? Who destroyed his heaps of rye? Who dragged him into court?–and yet you try to put all the blame on his shoulders. You are behaving very badly yourself, and for that reason you are wrong. I did not act in such a manner, and certainly I never taught you to do so. I lived in peace with Gavryl’s father all the time we were neighbors. We were always the best of friends. If he was without flour his wife would come to me and say, ‘Diadia Frol [Grandfather], we need flour.’ I would then say: ‘My good woman, go to the warehouse and take as much as you want.’ If he had no one to care for his horses I would say, ‘Go, Ivanushka [diminutive of Ivan], and help him to care for them.’ If I required anything I would go to him and say, ‘Grandfather Gordey, I need this or that,’ and he would always reply, ‘Take just whatever you want.’ By this means we passed an easy and peaceful life. But what is your life compared with it? As the soldiers fought at Plevna, so are you and Gavryl fighting all the time, only that your battles are far more disgraceful than that fought at Plevna.”

The old man went on: “And you call this living! and what a sin it all is! You are a peasant, and the head of the house; therefore, the responsibility of the trouble rests with you. What an example you set your wife and children by constantly quarrelling with your neighbor! Only a short time since your little boy, Taraska, was cursing his aunt Arina, and his mother only laughed at it, saying, ‘What a bright child he is!’ Is that right? You are to blame for all this. You should think of the salvation of your soul. Is that the way to do it? You say one unkind word to me and I will reply with two. You will give me one slap in the face, and I will retaliate with two slaps. No, my son; Christ did not teach us foolish people to act in such a way. If any one should say an unkind word to you it is better not to answer at all; but if you do reply do it kindly, and his conscience will accuse him, and he will regret his unkindness to you. This is the way Christ taught us to live. He tells us that if a person smite us on the one cheek we should offer unto him the other. That is Christ’s command to us, and we should follow it. You should therefore subdue your pride. Am I not right?”

Ivan remained silent, but his father’s words had sunk deep into his heart.

The old man coughed and continued: “Do you think Christ thought us wicked? Did he not die that we might be saved? Now you think only of this earthly life. Are you better or worse for thinking alone of it? Are you better or worse for having begun that Plevna battle? Think of your expense at court and the time lost in going back and forth, and what have you gained? Your sons have reached manhood, and are able now to work for you. You are therefore at liberty to enjoy life and be happy. With the assistance of your children you could reach a high state of prosperity. But now your property instead of increasing is gradually growing less, and why? It is the result of your pride. When it becomes necessary for you and your boys to go to the field to work, your enemy instead summons you to appear at court or before some kind of judicial person. If you do not plow at the proper time and sow at the proper time mother earth will not yield up her products, and you and your children will be left destitute. Why did your oats fail this year? When did you sow them? Were you not quarrelling with your neighbor instead of attending to your work? You have just now returned from the town, where you have been the means of having your neighbor humiliated. You have succeeded in getting him sentenced, but in the end the punishment will fall on your own shoulders. Oh! my child, it would be better for you to attend to your work on the farm and train your boys to become good farmers and honest men. If any one offend you forgive him for Christ’s sake, and then prosperity will smile on your work and a light and happy feeling will fill your heart.”

Ivan still remained silent.

The old father in a pleading voice continued: “Take an old man’s advice. Go and harness your horse, drive back to the court, and withdraw all these complaints against your neighbor. To-morrow go to him, offer to make peace in Christ’s name, and invite him to your house. It will be a holy day (the birth of the Virgin Mary). Get out the samovar and have some vodki, and over both forgive and forget each other’s sins, promising not to transgress in the future, and advise your women and children to do the same.”

Ivan heaved a deep sigh but felt easier in his heart, as he thought: “The old man speaks the truth;” yet he was in doubt as to how he would put his father’s advice into practice.

The old man, surmising his uncertainty, said to Ivan: “Go, Ivanushka; do not delay. Extinguish the fire in the beginning, before it grows large, for then it may be impossible.”

Ivan’s father wished to say more to him, but was prevented by the arrival of the women, who came into the room chattering like so many magpies. They had already heard of Gavryl’s sentence, and of how he threatened to set fire to Ivan’s house. They found out all about it, and in telling it to their neighbors added their own versions of the story, with the usual exaggeration. Meeting in the pasture-ground, they proceeded to quarrel with Gavryl’s women. They related how the latter’s daughter-in-law had threatened to secure the influence of the manager of a certain noble’s estate in behalf of his friend Gavryl; also that the school-teacher was writing a petition to the Czar himself against Ivan, explaining in detail his theft of the perchbolt and partial destruction of Gavryl’s garden–declaring that half of Ivan’s land was to be given to them.

Ivan listened calmly to their stories, but his anger was soon aroused once more, when he abandoned his intention of making peace with Gavryl.

As Ivan was always busy about the household, he did not stop to speak to the wrangling women, but immediately left the room, directing his steps toward the barn. Before getting through with his work the sun had set and the boys had returned from their plowing. Ivan met them and asked about their work, helping them to put things in order and leaving the broken horse-collar aside to be repaired. He intended to perform some other duties, but it became too dark and he was obliged to leave them till the next day. He fed the cattle, however, and opened the gate that Taraska might take his horses to pasture for the night, after which he closed it again and went into the house for his supper.

By this time he had forgotten all about Gavryl and what his father had said to him. Yet, just as he touched the door-knob, he heard sounds of quarrelling proceeding from his neighbor’s house.

“What do I want with that devil?” shouted Gavryl to some one. “He deserves to be killed!”

Ivan stopped and listened for a moment, when he shook his head threateningly and entered the room. When he came in, the apartment was already lighted. His daughter-in-law was working with her loom, while the old woman was preparing the supper. The eldest son was twining strings for his lapti (peasant’s shoes made of strips of bark from the linden-tree). The other son was sitting by the table reading a book. The room presented a pleasant appearance, everything being in order and the inmates apparently gay and happy–the only dark shadow being that cast over the household by Ivan’s trouble with his neighbor.

Ivan came in very cross, and, angrily throwing aside a cat which lay sleeping on the bench, cursed the women for having misplaced a pail. He looked very sad and serious, and, seating himself in a corner of the room, proceeded to repair the horse-collar. He could not forget Gavryl, however–the threatening words he had used in the court-room and those which Ivan had just heard.

Presently Taraska came in, and after having his supper, put on his sheepskin coat, and, taking some bread with him, returned to watch over his horses for the night. His eldest brother wished to accompany him, but Ivan himself arose and went with him as far as the porch. The night was dark and cloudy and a strong wind was blowing, which produced a peculiar whistling sound that was most unpleasant to the ear. Ivan helped his son to mount his horse, which, followed by a colt, started off on a gallop.

Ivan stood for a few moments looking around him and listening to the clatter of the horse’s hoofs as Taraska rode down the village street. He heard him meet other boys on horseback, who rode quite as well as Taraska, and soon all were lost in the darkness.

Ivan remained standing by the gate in a gloomy mood, as he was unable to banish from his mind the harassing thoughts of Gavryl, which the latter’s menacing words had inspired: “Something will burn with greater fierceness in Ivan’s household before long.”

“He is so desperate,” thought Ivan, “that he may set fire to my house regardless of the danger to his own. At present everything is dry, and as the wind is so high he may sneak from the back of his own building, start a fire, and get away unseen by any of us.

He may burn and steal without being found out, and thus go unpunished. I wish I could catch him.”

This thought so worried Ivan that he decided not to return to his house, but went out and stood on the street-corner.

“I guess,” thought Ivan to himself, “I will take a walk around the premises and examine everything carefully, for who knows what he may be tempted to do?”

Ivan moved very cautiously round to the back of his buildings, not making the slightest noise, and scarcely daring to breathe. Just as he reached a corner of the house he looked toward the fence, and it seemed to him that he saw something moving, and that it was slowly creeping toward the corner of the house opposite to where he was standing. He stepped back quickly and hid himself in the shadow of the building. Ivan stood and listened, but all was quiet. Not a sound could be heard but the moaning of the wind through the branches of the trees, and the rustling of the leaves as it caught them up and whirled them in all directions. So dense was the darkness that it was at first impossible for Ivan to see more than a few feet beyond where he stood.

After a time, however, his sight becoming accustomed to the gloom, he was enabled to see for a considerable distance. The plow and his other farming implements stood just where he had placed them. He could see also the opposite corner of the house.

He looked in every direction, but no one was in sight, and he thought to himself that his imagination must have played him some trick, leading him to believe that some one was moving when there really was no one there.

Still, Ivan was not satisfied, and decided to make a further examination of the premises. As on the previous occasion, he moved so very cautiously that he could not hear even the sound of his own footsteps. He had taken the precaution to remove his shoes, that he might step the more noiselessly. When he reached the corner of the barn it again seemed to him that he saw something moving, this time near the plow; but it quickly disappeared. By this time Ivan’s heart was beating very fast, and he was standing in a listening attitude when a sudden flash of light illumined the spot, and he could distinctly see the figure of a man seated on his haunches with his back turned toward him, and in the act of lighting a bunch of straw which he held in his hand! Ivan’s heart began to beat yet faster, and he became terribly excited, walking up and down with rapid strides, but without making a noise.

Ivan said: “Well, now, he cannot get away, for he will be caught in the very act.”

Ivan had taken a few more steps when suddenly a bright light flamed up, but not in the same spot in which he had seen the figure of the man sitting. Gavryl had lighted the straw, and running to the barn held it under the edge of the roof, which began to burn fiercely; and by the light of the fire he could distinctly see his neighbor standing.

As an eagle springs at a skylark, so sprang Ivan at Gavryl, saying: “I wi